It would be a pity for anyone who enjoys drinking wine not to experience Turkish wines. Tasting a variety of Turkish wines could be an indulging experience for wine lovers who not only opt for their habitual preferences, but who are at the same time in quest of different tastes as well. On the other hand, knowing where to drink and what to drink in Istanbul is naturally an important issue in the case of wine. The main intention of this post is to make a restaurant recommendation for such an experience among numerous others in the city. However, before that, I believe providing a background on the history of viticulture and wine production on these lands is worthwhile.

Anatolia is geographically in the vicinity of the area which is considered as the birth place of viticulture and wine making (vinification). Scientific findings mark Georgia, south of the Caucasus Mountains, as the first location of viticulture on earth, 7000 years ago. It is believed that cultivation of vines then sprawled to Armenia, Azerbaijan, Anatolia, Greece, Iran, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria. Viticulture and wine making was later introduced to Europe by Phoenicians and Greeks in antiquity.

Archaeological excavations provide evidence for the existence of wild grapes in two locations in Anatolia in the Neolithic era (circa 10000-6000 BC) but, no sign of cultivated vines. The two sites are namely, Nevali Çori-Şanlıurfa in the south-east and Canhasan III–Karaman in the south region. Findings in the Chalcolithic era (circa 6000-3000 BC) sites have mostly led to similar results as well with only one exception. The grape seeds that were discovered at Hassekhöyük, a tumulus in Şanlıurfa-Siverek, were considered as the first signs of viticulture in Anatolia. Bowls and cups from this time period have further reinforced the proposition that cultivation of vines and wine production started and developed around this time in Anatolia.

The Hatti were aboriginal people in Central Anatolia. Golden wine cups and beak-lipped jugs found in king tombs at Alacahöyük in this region were dated to mid-3000 BC. These findings that are exhibited at the Museum of Anatolian Civilisations in Ankara also show that drinking wine was a widespread tradition among the higher classes of the society at the time. Grape harvests are mentioned in trade documents written in cuneiform dated to circa 2000 BC. Around this time, the Hittites emerged in Anatolia where they later founded an empire that prevailed between 1650-1190 BC. Experts assert that the Hittite code of law has plenty of articles on penalties related to vineyards, vine trellises (supports) and wine.

Found in Arslantepe, Malatya–Turkey

(Source: tarihdergi.com)

Scientists classify the Hittite language as a part of the Indo-European language group. Archaeologists state that a town by the name of Wiyanawanda, which literally means Winetown, is mentioned in Hittite documents. The word wiyana for wine is firmly believed to be the source of the corresponding words such as wine, vin, vino in European languages.

In the 8th century BC, the great epic poet Homer, widely acclaimed for the timeless Iliad and Odyssey, refers to a wine Pramnos (or Pramnios) in both of his literary work. Probably born in Smyrna (today’s Izmir in West Anatolia), Homer was well acquainted with both coasts of the Aegean Sea. Therefore, he can be considered as a reliable witness to the wine culture that prevailed in Anatolia at the time. The renowned historian, geographer and philosopher Strabon (64 BC-24 AD) also mentioned the consumption of the Pramnos wine in Smyrna in later centuries. The ancient city of Clazomenae (today’s Urla, close to Izmir) was famous for its wine during the Roman rule in Anatolia. Currently, the area is one of the prominent areas of viticulture and vinification in Anatolia. The facilities of some of the well-known wine producers in Turkey are located in Urla.

(Source: tarihdergi.com)

The Hittites, the Phrygians, the Greeks and the Romans have all contributed to the improvement of vinification in Anatolia. Monasteries became important in wine production during the reign of the Byzantine Empire.

Wine production was continued especially by the non-Muslim subjects of the Ottoman reign. There is no information about the prohibition of wine consumption by the Ottomans until the 16th century. Later prohibitions were only for the Muslim population. However, these were far from deterring even them. According to Hans Dernschwam, a German traveller who came to Istanbul in 1550, from time to time the janissaries in the capital became so drunk in spite of the alcohol ban that they were punished. Stephan Gerlach, a German Lutheran theologian who visited Istanbul on a special mission at the end of the 16th century, also points out that drinking was a widespread activity among Turks at the time.

Ottoman Sultans had varied approaches to drinking despite the strict prohibition by Islam. It is known that some Sultans were fond of wine and other alcoholic beverages. This is most unusual since Ottoman Sultans became Caliphs of the Sunni Muslim world as of 1517. However, periods of freedom could be followed by those of severe prohibition. For example, Sultan Selim II (r. 1566-1574), the son of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566), was such a heavy drinker that he lost his balance at the hamam (Turkish bath) of the palace and died. Sultan Murat III (r. 1574-1595) who ascended the throne after his father, announced very strict rules against alcohol consumption. However, the greatest prohibition in Ottoman history was during the time of Sultan Murat IV (r. 1623-1640) even though he himself was very fond of drinking.

(Source: tarihdergi.com)

The 19th century was a time of reforms and pro-Western changes in the Ottoman Empire. These changes caused a deep dichotomy in the society. While conservatism and bigotry continued, a considerable number of Muslim elites acquired a secular outlook concerning the future of the country and thereby adapted themselves to Western ways of living. This no doubt also had an effect on wine production and consumption. However, the greatest booster for the sector was as a result of an outbreak of the phylloxera epidemic in 1862 in France. Originally from North America, phylloxera was carried to Europe by English botanists. Having first destroyed the vineyards in England, the epidemic moved to the continent and destroyed almost all the viticulture in 20-25 years. This created a great opportunity for Ottoman wine exporters because the phylloxera epidemic never reached their lands. Consequently, wine production surged and reached between 80 to 100 million litres in the 1880s. This amount further increased to 304 million litres in 1904. Today, Turkey’s domestic wine production is approximately 80 million litres.

The Great Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey following the Lausanne Treaty in 1923 was a blow on the wine industry as a considerable number of wine producing Greeks living in Anatolia left the country. The Turks who came in exchange were mainly tobacco farmers. In 1927, the Turkish state decided to support viticulture and vinification in the country. Foreign experts were invited to the Turkish Republic. The first state-owned wine factory was inaugurated in 1931, in Tekirdağ while privately owned producers were also licensed at the same time. Having led the industry by setting an example with several other succeeding plants across the country, the state eventually diminished and stopped production after 1945 while the private sector developed between 1950-1960. The import of foreign beer as of the beginning of the 1970s was a further setback for the industry as masses preferred it as a cheaper alternative to wine. In mid-1980s, the integration of the Turkish economy with the world on the one hand and the increasing popularity of Turkey as a mass tourism destination on the other, enlivened the wine industry again. However, the Turkish wine industry is currently suffering under the administration of an ideologically strictly alcoholic beverages averse government. Numerous restrictions, bans, fines and very high tax rates are the main obstacles that wine producers have to tackle. According to the data provided by Turkey’s Ministry of Agriculture, wine production was 65 million litres in 2023 in Turkey compared with 75 million litres in 2018.

In spite of all the impediments, some Turkish wine producers have made remarkable achievements in the international arena by participating and winning prizes in acclaimed competitions. Some of the brands in this group are Kavaklıdere, Suvla, Sarafin, Chamlija, Chateau Kalpak, Porta Caeli, Yedi Bilgiler (7 Bilgeler) in case you would like to try some of them.

Turkey has a vast potential in the field of wine production. Experts state that currently there are 1459 different grape types in Anatolia out of which 40 of these are suitable for wine production. A handful of dedicated experts on the subject are trying to revive the production of wine from indigenous grape species of Anatolia that have long been prone to disappearance. Mr. Levon Bağış is one of these dedicated specialists. He is one of the founders of Heritage Vines of Turkey, a movement that aimed to protect the hereditary vineyards of Anatolia in the last one hundred years. Furthermore, he is one of the partners of Yaban Kolektif which is a brand that is intent on revivifying Anatolian grapes by producing special wines. In addition to these, Mr. Bağış is also the founding-partner of a special wine-bar, FOXY Local & Real in Istanbul. Apparently, the bar is named after a characteristic that is attributed to the Concord grape by wine experts. According to them, this type of grape has a smell reminiscent of the musty smell of wet animal fur and a taste of cherry flavoured candy.

Nişantaşı

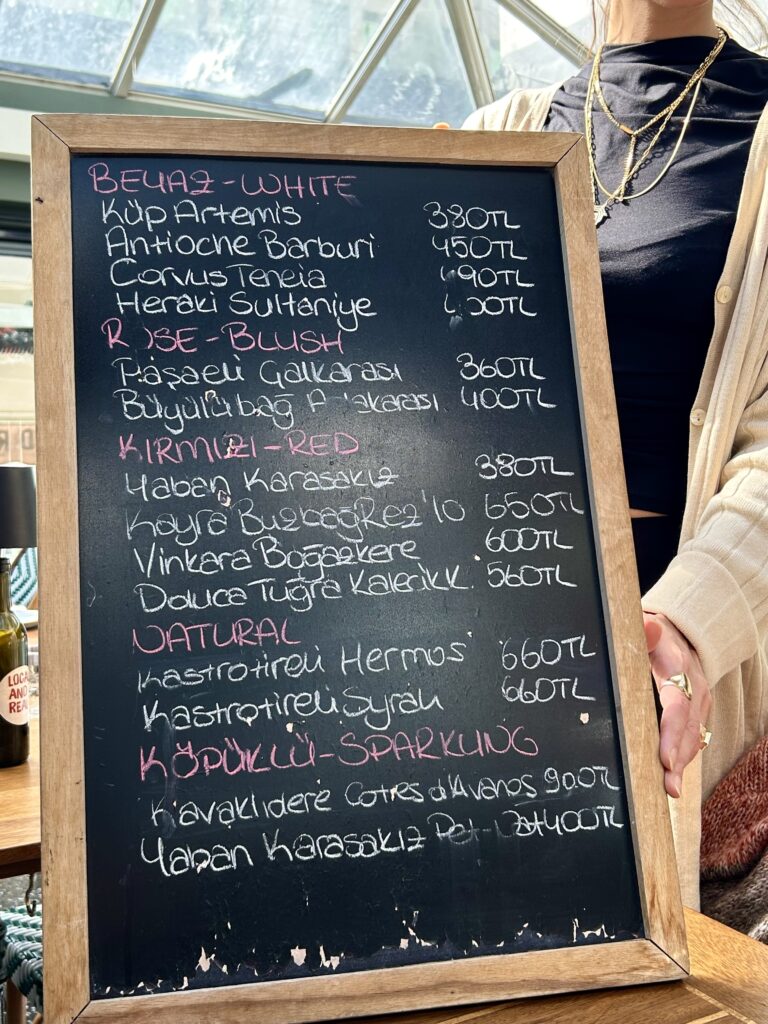

Foxy wine bar is located in the Nişantaşı district of Istanbul, at the address Mim Kemal Öke Avenue, No:1/D. Having opened its doors in 2019, Foxy Nişantaşı defines itself as the only natural wine-bar and bistro in Turkey where special wines produced from local grapes are served. The restaurant is among the recommended restaurants by Michelin in Istanbul. Foxy’s other founding-partner Maksut Aşkar is also the chef of the Michelin double starred (one for high quality cooking and a Michelin green star for being conscientious about environment and sustainable gastronomy) Neolokal. You can therefore be sure to sip your wine at Foxy with some delicious food. The evening menu offers a wider selection of choices than the lunchtime one. (You can follow the links for more information about both restaurants.)

The menu at Foxy is a pleasant combination of traditional plates and contemporary interpretations, cooking techniques and presentation. Sharing is highly recommended in order to be able to taste more specialties. Staff is helpful in making a selection from the menu and recommending matching wines that are both produced by Levon Bağış’s Yaban Kolektif and other small producers that he and his friends support.

Here is a proposed selection of delicious plates from the menu that has been tasted by the blogger:

Cold Dishes:

– “Humus”, Fresh Herbs and Lor Cheese Salad

– “Aylak Lakerda” (Cured Bonito)

– Mortadella, Smoked Bacon and “Sucuk”

Hot Dishes:

– “Seray’s” Signature Liver

– Grilled Octopus, Crispy Potatoes

– Duck Breast, Spicy Rice Pilaf with Chestnut

Dessert:

Crispy Pumpkin, Clotted Cream Sauce with Tahini

Wines:

White: Antioche Barburi. (Barburi grape is an indigenous grape of Antakya in south-east Turkey.)

Red: Yaban Karasakız. (Karasakız is another indigenous grape that grows in the Thrace region of Turkey.)

To share this post

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author