Often described by the almost stereotypical expression of being “the cradle of civilisations”, Turkey justifies the statement by its very location. The country stretches across lands that have been home to a multitude of different civilisations over millennia. While mostly popular with its ancient Greek and Roman sites, archaeological excavations have proven that Turkey is home to a vast number of historical remains that are dated beyond antiquity. The country’s transportable archaeological findings are displayed in the increasing number of state-of-the art museums across Turkey. The Istanbul Archaeological Museums complex has a special place among these museums because, apart from the invaluable objects it houses, it is the first archaeological museum of Turkey.

The Istanbul Archaeological Museums complex consists of three main museums on the same premises. As you enter the garden, a grand building on your right will immediately catch your eye. This is the Archaeological Museum. The more modest building on your left is the Museum of Ancient Orient. Further down in the garden, facing the main building, there is a much older Ottoman structure that is today called the Tiled Kiosk Museum. The collection in this latter building does not currently consist of archaeological findings but the pavilion once served as an archaeological museum before a proper museum was built. With more than one million artefacts in total, each of the museums deserve separate attention and maybe even visits that extend over several days. However, a visit to this group of museums is highly recommended even if your time in Istanbul is limited. The collection possesses some unforgettable rare pieces that are part of world history and heritage. Note that, the findings on display here are from the Ottoman lands of the time and have therefore been legally excavated and transported to Istanbul. As it is known, this is not always the case for the collections of some of the renowned archaeological museums across the world.

There are two ways to go to the Archaeological Museums complex. One of these is through the first courtyard of the Topkapı Palace which is open to public. Upon entering the courtyard through the Bab-ı Hümayün (Imperial) Gate, on your left you will see a Byzantine church. This is the church of the Divine Peace, Haghia Eirene. The building was used to store archaeological findings for a while, before the construction of the museums. Heading past the church towards the gate on the left side of the first courtyard, you will be leaving the palace grounds through the Gate of the Watchmen of the Girls. As you do, the building that you see on your left is the Darphane which is the former Ottoman Imperial Mint and Treasury. The narrow cobble stone road that goes downhill takes you to the public Gülhane Park. The Archaeological Museums complex is halfway down this slope, to your right. However, this route is not accessible on the days that the Topkapı Palace is officially closed. In that case, facing the entrance to the palace, you will have to follow the road to your left that runs along the outer wall of the palace. This is the Soğukçeşme Street which also goes down the hill, leading you past the Sarnıç Fine Dining Restaurant that was mentioned in an earlier post. (You can click on the link for quick access to the related post.) Having reached the Gülhane Park at the bottom of the hill, follow the signs that will lead you inside the park and then uphill again, to the museum complex. As you may have noticed, the above-mentioned instructions assume that the visitor is in the vicinity of the Topkapı Palace and Haghia Sophia, both at the Sultanahmet Square. On the other hand, if you are by the shore in Eminönü or Sirkeci, you only need to get to the Gülhane Park from there. The signs at the entrance and inside the park will take you to your destination.

Museum of Ancient Orient

It might be of interest to briefly refer to the traditon of collecting artefacts and notable items by the Ottoman state before delving more on the Archaeological Museum’s collection. Ottoman rulers have been keen on collecting historical items of value since the time of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror. However, the process of collecting and preserving antiquities was not systematic until 1846. This was when Fethi Ahmet Pasha, who was the son-in-law of the late Sultan Mahmut II, began gathering antiquities from all over the imperial lands and storing them in the church of Haghia Eirene in the first courtyard of the Topkapı Palace. Fethi Pasha organised the collection in two distinct parts. The Ancient Weapons collection was later to become the nucleus of the Military Museum. The Antiquities collection on the other hand constituted the basis of the Imperial Museum which was founded in 1869. This collection and other antiquities acquired later on were transferred to the Tiled Kiosk in 1874. Serious attempts to classify and catalogue the items were made during the following decade. Great effort was also made to control the illegal outflow of the antiquities and treasures of the empire which were being looted by European archaeologists and collectors.

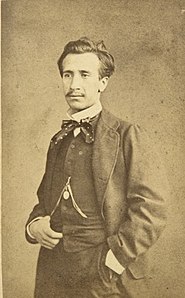

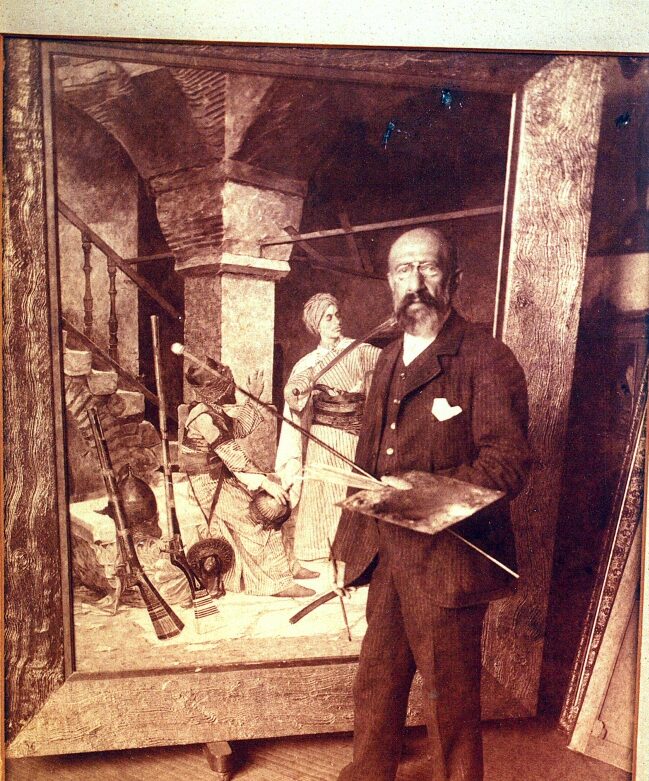

The turning point for the museum was when Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910) was appointed as director in 1881. Osman Hamdi Bey was the son of Ibrahim Edhem Pasha who was an Ottoman Grand Vizier of Greek origin from the island of Chios. Osman Hamdi himself was an Ottoman intellectual, administrator, painter, art expert and an accomplished archaeologist. He is also considered as the founder of modern museology in Turkey. As a young man, he initially studied law (first in Istanbul, later in Paris). However, while pursuing his academic studies in Paris (where he stayed for nine years) he left the law program and decided to concentrate on painting. He took lessons from the French Orientalist painters Jean-Léon Gérôme and Gustave Boulanger. You can come across his paintings at various museums in Istanbul including the National Palaces Painting Museum in Beşiktaş and the Pera Museum in Tepebaşı. Osman Hamdi Bey is the founder of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum as well as of the Academy of Fine Arts (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi), known today as the Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts. Quite surprisingly, he was also the first mayor of the district of Kadıköy on the Asian side of Istabul.

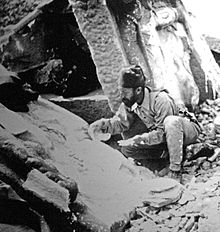

As an archaeologist, he conducted the first scientific excavations by a Turkish team. Among his excavations are the Commagene tomb-sanctuary on Mount Nemrut (today a UNESCO World Heritage and an important tourist attraction site in southeast Anatolia) and the Hekate sanctuary in Lagina (in southwest Anatolia). However, his most memorable findings were those in Sidon, Lebanon. The sarcophagi that he discovered there between 1887-1888 are still the most precious items at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The sarcophagi that he discovered in the hypogea (plural of hypogeum-meaning underground necropolis) in Sidon were retrieved by means of rails that were built from the underground excavation sites to the ground level. The mesmerising Alexander the Great Sarcophagus, the Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women, the Sarcophagus of King Tabnit are all findings from the Royal Necropolis of Sidon.

After buying your tickets at the booth and entering the Istanbul Archaeological Museums’ grounds, the first building you will see on your left is currently the Museum of Ancient Orient. The building itself was once the Academy of Fine Arts when founded by Osman Hamdi Bey. It was the work of art of the Ottoman Levantine architect Alexander Vallaury (1850-1921) who himself was the first professor in the architecture department of the academy. Today, the building houses archaeological findings from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and pre- Islamic Arabian Peninsula. Among many tablets on display in cuneiform there is the Kadesh Peace Treaty which is the earliest known peace treaty in history. The treaty was between the Hittite King Hattusilis III and the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II in 1269 B.C. It was written in Akkadian, the international language of the time. Three main versions in Akkadian were discovered in 1906, by Hugo Winckler and Teodor Makridy, in the capital city of the Hittites Hattuşaş/Boğazköy, Turkey. This was a Turkish-German joint excavation. One of these treaty documents is currently in Berlin. The two remaining ones are part of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums collection. The Egyptian version was carved on the walls of two temples in Egypt: the Amon at Karnak and the Ramesseumat Luxor. These versions were slightly altered to give a greater emphasis to the role of Egypt in establishing peace.

The earliest known peace treaty in history

Hattuşaş/Boğazköy, Turkey

Museum of Ancient Orient

Relief Orthostat. Late Hittite period (8th Century B.C.)

Sam’al (Zincirli Höyük), Gaziantep, Turkey

Museum of Ancient Orient

Relief Orthostat, (744-727 B.C.)

Hadatu (Aslantaş), Syria

Museum of Ancient Orient

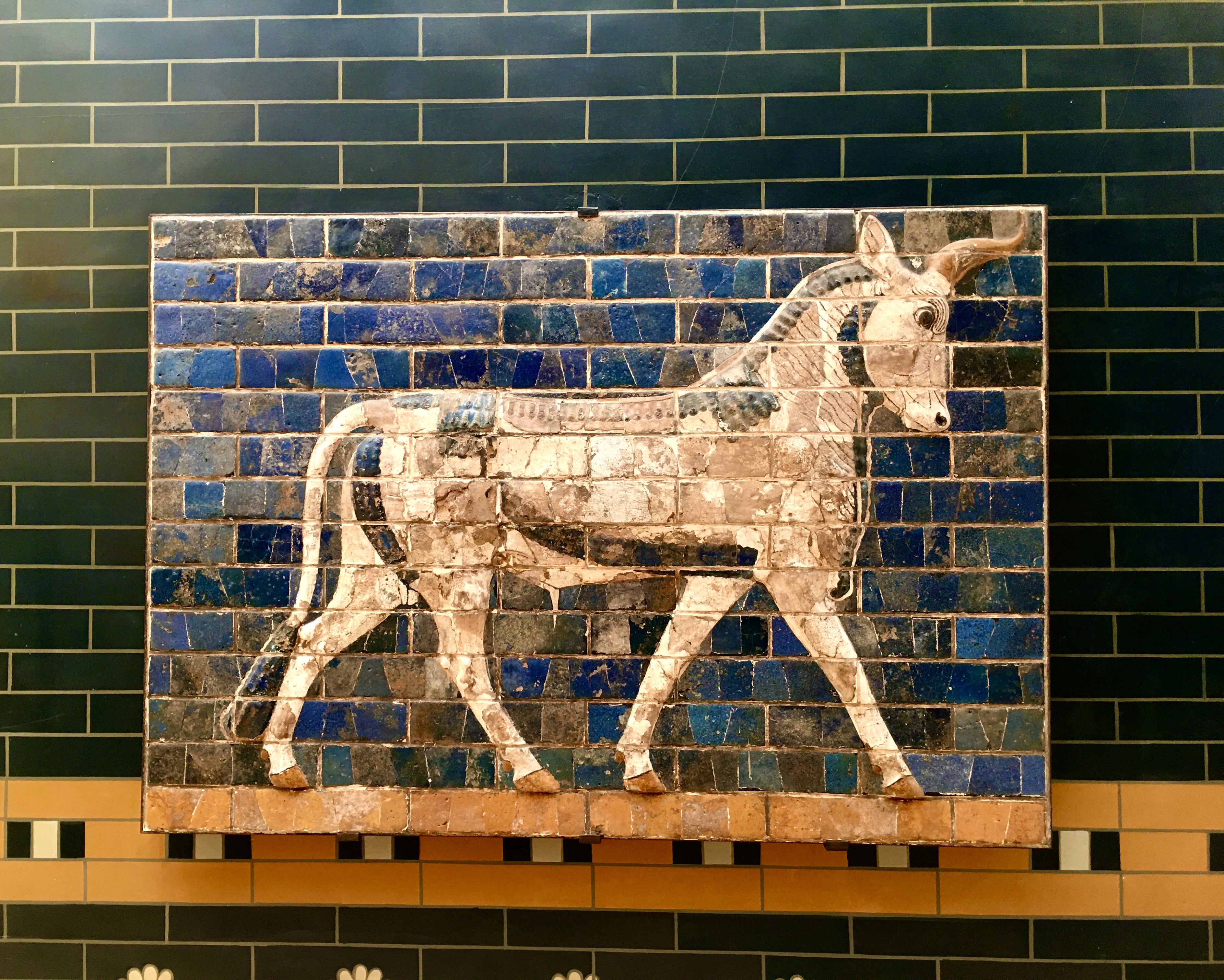

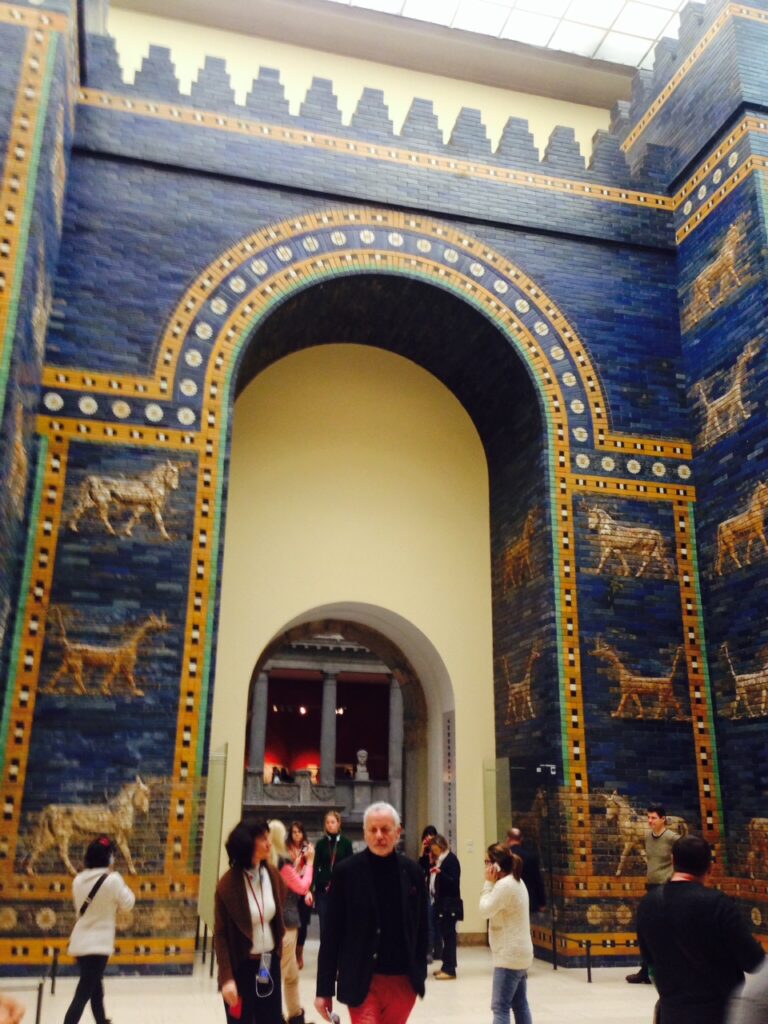

The ceramic wall panels from the Ishtar Gate of Babylon are no doubt noteworthy as well. However, the wall panels that are on display here, although extremely beautiful, fail to give an idea about the true grandeur of the Ishtar Gate. The Ishtar Gate was the 8th gate to the inner city of Babylon and was built in 575 B.C. by the commission of King Nebuchadnezzar II. While Osman Hamdi Bey was only able to bring the panels on display at the Museum of Ancient Orient, the German archaeologists Robert Koldeway and Walter Andrae excavated the site between 1904-1914 and smuggled the currently displayed gate at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin with the help of the German intelligence and local Iraqi tribe sheikhs. The Ottoman authorities were unaware of the whole operation. The gate was disassembled and numbered to be reassembled again in Berlin in 1918.

Museum of Ancient Orient

After the findings of Osman Hamdi bey in Sidon and other sites on Ottoman lands, the need for a new and proper museum building soon became evident. It was decided to build a big museum right across from the Tiled Kiosk. The building in neo-classical style was also built by Alexander Vallaury. The museum opened its doors to the public on June 13th, 1891. However, soon this elegant building also turned out to be inadequate and two additional wings were built and opened in 1902 and 1908. This building, which is itself now called the Archaeological Museum within the complex, went through a recent renovation and restoration during the past decade. Some sections are still closed to the public due to continuing work. The recently opened sections reveal a renewed and state-of-the- art concept of museology. Hopefully, the Museum of Ancient Orient will also undergo a similar renovation in the near future to become on par with this main building.

Museum of Ancient Orient

Museum of Ancient Orient

The halls of the Archaeological Museum are full of treasures to explore and admire. The few mentioned here are only the most prominent ones. Having said that, it would be fair to start with the Alexander the Great Sarcophagus which has a well-deserved worldwide acclaim. Found at the royal underground necropolis (in the third chamber of Hypogeum A) in Sidon, in actual fact it does not belong to Alexander the Great. The reason why it acquired this name over the years is because of the beautiful depictions of Alexander the Great on the sarcophagus. The ruler resting in the sarcophagus is said to be King Abdalonymos who was the last ruler of Sidon in Lebanon. Dated to 312-307 B.C., the Alexander Sarcophagus is believed to be the most recently built tomb in the underground cemetery.

Egyptian deity known as the protector of mothers, childbirth, children, households and fertility (7th-6th Century B.C.), Amathus, Cyprus Archaeological Museum

Archaeological Museum

One of the long and the short sides depict war scenes while on the other two, there are hunting scene representations. They are carved in high relief and were once painted. Traces of paint on some of the figures can still be detected if carefully observed. Abdalonymos was distantly related to the royal family of Sidon. He was appointed as ruler by General Hephaestion who, after the Battle of Issus, was to assign the city’s king by the order of the Macedonian King Alexander the Great. The facades of the sarcophagus depict important events in King Abdalonymos’s life. The war scenes are from the Battle of Issus after which he became king and Alexander was able to conquer Syria.

Archaeological Museum

Another beautiful item from Sidon is the Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women, dated to circa 350 B.C. The name comes from the beautifully depicted mourning women on its facades. Unfortunately, the tomb was looted long before its discovery by Osman Hamdi Bey. There are two versions of explanations for the mourning women on the sarcophagus. According to one, the women simply represent the general tradition of mourning in Mesopotamia and the Middle East. The second one claims that the women are the wives or relatives of the deceased who is thought to be King Straton I (374-358 B.C.).

Archaeological Museum

Archaeological Museum

The Lycian Sarcophagus takes its name from its shape which is typical of the Greco-Anatolian art reflected in Lycian tombs. Found in the same underground necropolis, it belongs to an unidentified ruler of Sidon in late 5th century B.C. On the long sides, you can see representations of lion and boar hunts while the short facades reflect fighting centaurs and sphinxes.

Archaeological Museum

The Sarcophagus of Tabnit is the oldest one among the unearthed sarcophagi at the Royal Necropolis of Sidon. It is dated to 6th century B.C. and belongs to King Tabnit of Sidon, as the name implies. The shape and the lid evoke the mummy of an Egyptian pharaoh. In fact, it is stated that the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the chest reveal that the sarcophagus initially belonged to an Egyptian commander whose name was Peneptah. Apparently, there is another inscription written in Phoenician under the first one which proves that the sarcophagus had been used a second time for King Tabnit.

Archaeological Museum

The above-mentioned sarcophagi from Sidon are not the only ones in the possession of the museum. There are plenty of others that were excavated in Anatolia. Among these, the fascinating Sidamara Sarcophagus is outstanding. It was found in central Anatolia, near Ambararası, Konya. It is believed to have been made in the 3rd century A.D. for a wealthy and prominent couple whose statues adorn the top of the lid. Most probably, they shared the sarcophagus when they died.

Karamanoğlu İbrahim Bey public soup kitchen, Karaman, Turkey

The Tiled Kiosk Museum

The last museum in the complex is the Tiled Kiosk Museum. The building itself is very important as it is the oldest surviving secular Ottoman building, dated to 1472. This beautiful building was built by the order of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror as an outer pavilion of the Topkapı Palace. The Kiosk takes its name from the beautiful tiles that adorn the building. The style and the calligraphy of the inscriptions, including the date of construction, allude to Persian design and taste. It is known that the area in front of the pavilion, where today stands the Archaeological Museum, was a large jirit field (a traditional polo like game of Turks) and the Tiled Kiosk seems to have been a kind of royal lodge to watch the games.

Iznik, Turkey

The Tiled Kiosk Museum

The Tiled Kiosk Museum

The Tiled Kiosk Museum

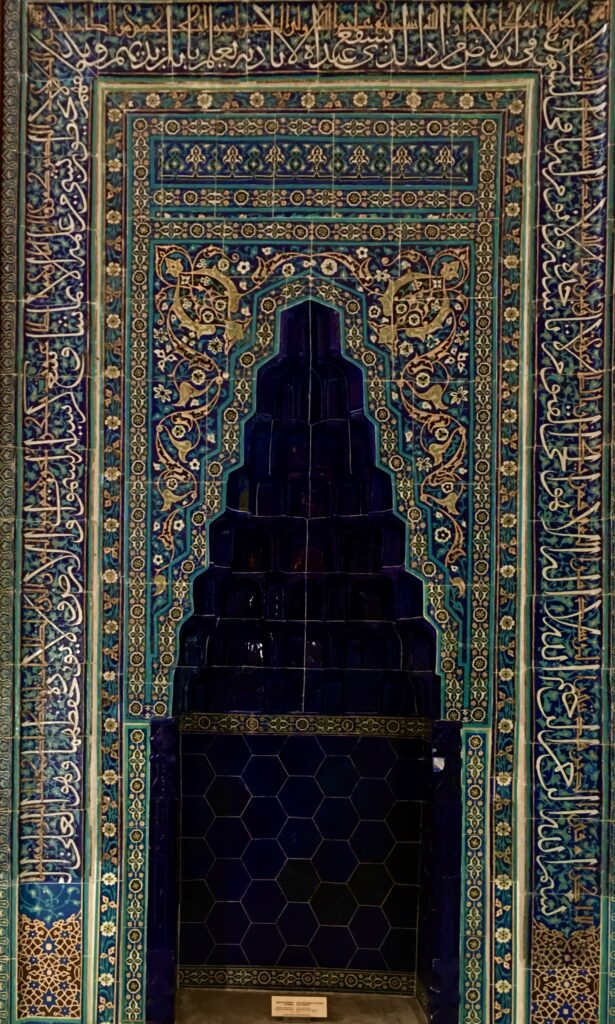

The Tiled Kiosk underwent a very long period of renovation until it was opened to public again a few years ago. It houses about 2000 tiles and ceramic artefacts from the 11th to the 20th centuries that cover the Seljuk and Ottoman periods. The tiled mihrab of the Karamanoğlu İbrahim Bey public soup kitchen (1432) and the Fountain of Elixir of Life (1590) are among the impressive items of the collection, in addition to the outstanding Iznik and Çanakkale tiles that are on display.