Istanbul has always been home to different religions, sects and nationalities. The existence of so many different communities has been the very essence of this city since ancient times. This is in fact why Istanbul is such an interesting and inspiring city. It is an ongoing quality that introduces new colonies of people depending on the political or social forces and events at a certain point in time. That is why, for example, you may encounter Iranian Christians, who fled their country after the revolution in 1979, singing Christmas carols and worshiping at a church in Beyoğlu. Likewise, you can taste the delicious and characteristic dishes of the Syrian cuisine in Istanbul after the flow of Syrian refugees in recent years. Some of these communities are temporary. They might choose Istanbul as a necessary stop before moving to other countries. But, there are always some who remain. They enrich the atmosphere of the city, unbeknown to even most of the natives of the city.

Among all the different groups in Istanbul, the Jewish community is the one that can definitely not be called transient. It is known that Jews have been present, both in Turkey and in Istanbul, for thousands of years. They are an inherent and invaluable part of the city even though they are not as visible as would be expected. You cannot easily walk into a synagogue as you can to major churches in the city. This is not because of a lack of hospitality or compassion on the part of Turkish Jews. Unfortunately, the numerous past terrorist attacks to these holy temples (some with serious fatal casualties) justify all the precautions that need to be taken. However, you can still visit them if you contact in advance and be sure to have your passports with you.

Whether under Byzantine, Ottoman or Turkish Republic rule, Jews have always been loyal to these lands. One has to admit that at times, due to state-imposed sanctions or provocations, life was not always easy for them. Each of these periods in history have their own respective skeletons in their cupboards regarding the treatment of their Jewish citizens. However, these incidents do not reflect the peaceful relationship of the Jewish community with the Muslim and Christian citizens of Istanbul and Turkey. The historic synagogues in some districts of Istanbul, such as Ortaköy and Kuzguncuk, that are right next to historic mosques and churches are a clear demonstration of this harmony among the people.

There is no definite information about the exact settlement date of Jews in Anatolia. However, it is known that, some of the Jews in Palestine migrated to Asia Minor and settled in various big cities of the Roman Empire. This was long before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D. Based on archaeological excavations, it is stated that there is evidence of Jewish communities in ancient cities as early as the 4th century B.C. Some of these cities are Ancyra (Ankara), Sardis (Sart), Hypaepe (Ödemiş), Aphrodisias (Karacasu-Aydın), Corykos (Mersin), Laodiceia (Pamukkale), Myndos (Gümüşlük) and Andriake (Antalya). According to the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37 A.D.-?), Aristotle (384 B.C.-322 B.C.) met and had long discussions with Jews when he travelled to Anatolia. Even the majority of native citizens of Turkey and Istanbul are ignorant about the thousands of years long existence of Jews in these lands. It is generally wrongfully thought that the Sephardic migration in the 15th century marks the beginning of Jewish existence in Istanbul and Turkey.

Source: www.wikipedia.org

During the Roman and Byzantine periods in Anatolia, there were considerable number of Jewish communities that were relatively well-integrated, with certain special privileges and legal immunities. Jews did suffer occasional restrictions and hostility under the Byzantine rule but, it is believed that these were not as severe as the systematic anti-Semitic oppression that they underwent in Western Europe at the time. Some Byzantine Emperors, the most important being Justinian I, did try to convert Anatolian Jews to Christianity. However, these attempts were to no avail.

The first synagogue in Istanbul is believed to have been built in 318 A.D., in the district of Halkopratia (Bakırcılar) which was the main residential area of Jewish coppersmiths. This synagogue was later converted into a church during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II (401 A.D.-450 A.D.). Naturally, other synagogues were built following this incident. Jews settled in the area between Hagia Sophia and today’s Bahçekapı, in Eminönü as of the 9th century. In fact, there was an entrance, by the name of Porta Iudece (Jewish Gate), to this Jewish district at the location close to where now stands the Yeni Cami mosque. In the 11th century, Jews were sent to Pera (roughly today’s Beyoğlu and Galata), on the opposite coast of the Golden Horn. The meaning of Pera (away in Greek) is a clear clue to the policy of sending Jews outside the city walls of Constantinople. At the end of the Latin period in Constantinople (1204-1261), Jews were relocated by the Byzantine Emperor Mikhail Palaiologos VIII to Vlanga (Langa) and Pegai (Kasımpaşa), by the Golden Horn. These districts were to stay as the main Jewish settlement locations until the Ottoman conquest in 1453. There is said to be still a small group of Romaniote Jews in Istanbul who are descendants of the Hellenistic Jews of the Byzantine era.

Another group from those times is the Karaite (or Karaim) Jews who migrated from Jerusalem to Constantinople in the 11th century, fleeing the turmoil caused by the First Crusade. They were originally a branch of Caspian Turks who converted to Judaism in the 8th century. In Constantinople, they lived around Eminönü, Edirnekapı, Galata and Karaköy. It is believed that the name of the Karaköy district comes from the Turkish words Karay Köyü which means Karaite village. Eminönü, across from Karaköy by the Golden Horn, was also densely populated with Karaites, alongside Romaniote Jews, until well after the Ottoman conquest. As stated above, the district was demolished for the construction of the Yeni Cami mosque in 1597. The Karaites in the area were relocated to Hasköy by the Sultan. Today, there is only one actively used Karaite synagogue in Turkey and that is the one in Hasköy. In line with their beliefs, this temple is located underground and serves the diminishing small number of Karaite Jews in Istanbul.

Source: www.salom.com.tr (9/10/2017)

The Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, from East Europe and Germany, lived alongside the Greek-speaking Romaniotes and the Karaite Jews (who spoke a Turkic language with Hebrew influence) under the Byzantine rule for centuries. The Ashkenazi Jews were always a small group (stated to be roughly 3%) within the Jewish community.

Source: www.wikipedia.org

The first encounter of Jews with Turks in Anatolia was during the Anatolian Seljuk Empire (1071-1308). they were granted freedom of worship and religion. In 1299, Osman Bey, a member of the Turkish Oğuz Kayı tribe, founded the Ottoman State at the border of the Byzantine Empire. With increasing conquests, the Ottomans were soon to become a nightmare for the Byzantines. When Osman’s son Orhan Bey conquered Bursa in1326, the Jews who had previously left the city returned and were encouraged to practice their professions. The Etz Ahayim Synagogue was repaired and opened to worship by a special decree of Orhan Bey. Jews welcomed and regarded the Ottomans as saviours in every city that was conquered by them.

Ottoman Empire (1779)

Source: www.wikipedia.org

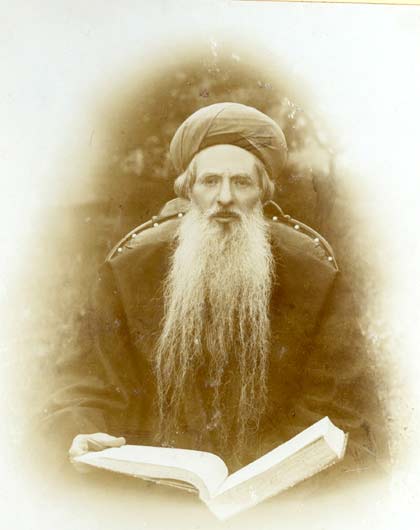

Between 1421 and 1453, the Jewish population on Ottoman lands increased considerably when Sultan Murat II accepted Ashkenaz groups from France. One of these immigrants was Rabbi Yitzhak Sarfati, German-born Jew of French descent, who became the Chief Rabbi of Edirne (Hadrianopolis), the then capital city of the Ottomans. In a letter addressed to the Jews of the Rhineland, Swabia, Styria, Moravia, France and Hungary he said, “Turkey is a land wherein nothing is lacking”… “Is it not better for you to live under Muslims than under Christians?”

The conquest of Constantinople was a turning point for Jews who were under Ottoman rule until then. Finding the city in a state of disarray due to the numerous sieges, the savage pillage of the Crusaders between 1204-1261 and the plague pandemic in 1347, Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror decreed its speedy recovery. The city had to regain its glory if it were to be the new capital of the empire as he had wished for a long time. To this end, he ordered the resettlement of not only Muslims but also Jews and Christians in the new capital. To his Jew subjects, his call was as follows:

“God has bestowed many countries to me and has commanded me to look after, to provide sustenance for, and protect the descendants of his disciples Prophets Abraham and Jacob… Who amongst you would like to come to the capital, Istanbul, with God’s help, and settle there under the shadows of fig trees and vineyards, to live in peace, to engage freely in commerce and to own property?”

Following this invitation, Romaniote Jews from all over the Ottoman lands in the Balkans and Anatolia migrated to Istanbul. They are thought to have made around 10% of the city’s population. Romaniotes became an influential community at the capital of the empire until the big wave of Sephardic Jew immigrants some decades later.

the Venetian architect G.J. Cornaro.

In 1470, still during the reign of Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror, there was also a major Ashkenazi immigration to Istanbul and other major cities of the empire when they were expelled by the Duke of Bavaria Louis IX. These immigrations from East Europe and Russia continued in the following centuries. However, Ashkenazi Jews always remained as a small group within the Jewish community in the country. Their preferred cities were mainly Istanbul and Izmir. Despite their small size, Ashkenazi Jews acquired important roles in the second half of the 19th century, in the areas of political and commercial relations between the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian Empires. They became influential, especially in the Galata district of Istanbul, in financial, educational and cultural areas.

capacity of 400 people

The most significant immigration wave of Jews to Ottoman lands and to Istanbul occurred in 1492, during the reign of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror’s son, Sultan Bayezid II. When the Spanish city Granada, which was the last citadel held by Muslims, fell on January 20th, 1492, the 781 years of Muslim rule in Spain came to an end. This big event had consequences for the Muslim and Jewish communities in those lands. First, they were forced to convert to Christianity to which some conceded. For those who refused, the King and Queen, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile signed the following at the Alhambra Palace, on March 31st, 1492:

“After thinking about it at length and pondering with a sober mind, we hereby order that any Jews that live within the boundaries of our Kingdom must leave the country with their wives, children and servants, no matter what age they may be and never return to these lands”

The given deadline was August 2nd, 1492. The frantic escape of the Jews from the Spanish Inquisition, that they would face if they stayed, caused the migration of thousands of Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal. The exact figure is not certain but it is generally agreed that around 120,000 Jews left the Iberian Peninsula. Others from Puglia and Sicily joined them, making a total of roughly 150,000 people. They left behind all their wealth, their houses and land in the hope of returning one day. This would never be possible until 523 years later, in 2015, Spain and Portugal offered an apology to the descendants of the expelled Sephardic Jews and gave them EU passports as an act of reconciliation.

At the time of this great expulsion, the Ottoman Empire was the only country that welcomed the displaced Sephardic Jews even though they had a different religion, culture, ancestry and language. Sultan Bayezid II signed and sent a decree to the governors across the Ottoman lands stating the following:

“Let alone to refuse entry to the Jews from Spain, they should be welcomed with complete open heartedness and whosoever acts in opposition to this by treating the immigrants with contempt or causes them harm in any way will be punished by death…”

The new Jewish community that arrived settled mainly in Thessaloniki, Sarajevo, Edirne, Nicopolis (Niğbolu)and Istanbul. Some settled in the western and northern Anatolian cities such as, Bursa, Aydın, Tokat, and Amasya. They surpassed in number the other Jewish communities that had already been living in those cities. Sephardic Jews are still the largest group among all Jewish communities in Istanbul. Keeping their culture and language, Ladino (Old Spanish of 15th century with some verb conjugations and words adapted from the local Turkish language), has been their challenge throughout centuries in these lands.

in the 19th century

Source: www.dailysabah.com (13/10/2017)

Centuries later, the young Turkish Republic provided shelter for another group of Jews. Although this time the number of immigrants was much smaller, the act was no less meaningful. Between the years 1933-1945, Turkey was home to mostly Jewish academicians who were forced to leave the Nazi Germany. Some of them were not Jews but were forced to leave because they opposed the regime. These groups of scientists played a crucial role in the foundation of universities (such as the Istanbul University) and several institutes in Turkey. Most of them left for the US after the war. Only a small group remained.

In 1989, 113 Turkish Jew and Muslim citizens founded the Quincentennial Foundation to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the immigration of Sephardic Jews in 1992. The foundation celebrated the event in the best possible way at that time, with numerous cultural, social and academic events. In line with its mission of making the historical humanitarian approach of the Turkish state and people towards Jews known both within Turkey and abroad, the Quincentennial Foundation has been continuing these activities. Some of the countries where these activities took place are the US, Canada, Mexico, France and England. One of the greatest deeds of the foundation has been the establishment of a museum. The Quincentennial Foundation Museum of Turkish Jews was initially founded in the Zulfaris Synagogue in 2001. In January 2016, the museum moved and reopened within the premises of the Neve Shalom Synagogue in Galata which is an historically important district for the Jews of Istanbul. The museum is located in three separate sections and it is independent from the synagogue. However, it is annexed to the temple by means of a glass passageway that leads to the ethnographic section of the museum. This enables visitors to see the interior of the Neve Shalom Synagogue and witness the religious ceremonies that are held there.

Every year, the European Day of Jewish Culture is celebrated in Istanbul together with 35 other countries. This is the day when the doors of some synagogues are open to people of all faiths. The main aim of the day and the activities that take place is to create an awareness of the Jewish culture, history, tradition and life and thereby to strengthen the ties among different cultures and communities in the city.

prayer for all nations”.

It is stated that currently there are more than twenty actively operating synagogues in Istanbul. A few of them are open only in summer or just for special occasions. The estimated number of Istanbulite Jews is currently around 15,000. Some historical synagogues have been closed down due to diminishing congregations over the years. All of these synagogues are part of the national heritage of Istanbul. It is important to find ways to preserve them, even if by modifying them for alternative uses. Schneidertempel is an excellent example for this type of renovation and preservation. Situated at the corner of Banker and Felek streets, Schneidertempel was originally the synagogue of the Guild of Ashkenazi Tailors of Istanbul. It was opened in September 8th, 1894 with the imperial permission and decree of Sultan Abdülhamid II. While the modest Schneidertempel, with its eclectic 19th century architecture, was the place of worship for tailors, artisans and craftsmen of the Ashkenazi community, the wealthier and more educated members preferred to go to the more prestigious and larger Great Ashkenazi Synagogue. In time, the size of the congregation of Schneidertempel and its importance declined due to the shift in the occupational distribution of the Ashkenazis. For a time, it was used as the administrative centre of the Istanbul Ashkenazi Community. Now, it is a Cultural Centre where numerous exhibitions, book launches and reading sessions have been hosted since 1998.

There is no doubt that Jews in general have contributed immensely to the modernisation movement in the Ottoman Empire since very early times. The first printing house in the Ottoman realm was established by Sephardic Jews. In 1492, Nahmias Brothers brought their printing equipment from Spain when they had to flee the Spanish Inquisition. The first book was printed in 1493. Ottoman Sultans entrusted their health and life to Jewish doctors. Many of them also served in the army as military doctors. Their engagement and dexterity in commerce enhanced the development of not just Istanbul but also other Ottoman cities such as Thessaloniki (Selanik), Hadrianopolis (Edirne), Smyrna (İzmir) and Damascus (Şam) as well. In time, wealthy Jews became chief financiers of the Ottoman court. Some of these bankers were later involved in politics through their collaborations with opposing groups such as the Young Turks. The influence of the Jewish community was not limited to these areas. Their impact on the educational, social and cultural aspects of life, as of the third quarter of the 19th century, sowed the seeds for the secular and modern republic that followed.

It is a fact that there has been a flow of emigration from the Turkish Jewish minority to Israel in recent years. According to the leaders of the community, the reasons are various. However, better opportunities for higher education and job opportunities for the young generation are stated to be the primary ones. A sense of insecurity due to the recent political atmosphere may be another. Whatever the reason, we hope that they will not forget Istanbul for Istanbul will not forget them…

———————————————-

Sources:

(1)- The Quincentennial Foundation Museum of Turkish Jews.

(2)- www.salom.com.tr

(3)- Güleryüz, N.A., “Tarihte Yolculuk-Edirne Yahudileri”.

(4)- Sumner-Boyd, H. and Freely, J., “Strolling Through Istanbul”.

(5)- Freely, J., “Istanbul The Imperial City”.