This is yet another current exhibition in the city that is in an historical setting. Maybe it is not so surprising when you reflect on how old this ancient city is and how abundant historical buildings are in Istanbul. It is good that these sites have lately become venues for such purposes; not only for visitors, but also for Istanbulites who get easily caught up in the fast pace of the city and tend to forget the true essence of the city.

“Blooming Flowers in Caria” is a very special Turkish carpet exhibition that can be visited until December 5th, 2019. The carpets on display are a part of the rich collection of Mr. Selçuk Mergen who is one of the leading experts in this area. Being a prominent business professional in this area for more than forty years, he did not miss the opportunity of collecting ancient and rare Turkish carpets. Thanks to a dear friend, I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Mergen personally and visiting the exhibition while listening to his detailed explanations about the carpets. I was very much impressed with the depth of his knowledge and his enthusiasm that seemed to be everlasting.

The historical site where the exhibition is taking place is the Şerefiye or Theodosius Cistern. This cistern which was discovered in 2010 is one of the many that exist under the Old City. Apart from the ones known by the general public such as the Basilica Cistern (Yerebatan) and the Philoxenus or A Thousand and One Columns Cistern (Binbir Direk), there are countless others under shops, hotels and old churches on the Historical Peninsula of Istanbul. For more information about these less known Byzantine cisterns, you can read my post “Historical Cisterns of Istanbul”.

The Şerefiye Cistern was built by the East Roman Emperor Theodosius II between 428-443 A.D. The purpose was to store the water that was brought from the Belgrade Forest via the Valens Aqueduct. The water was later to be distributed among the Nymphaeum, the Baths of Zeuxippus and the Great Palace. Located at Pierre Loti Street in the Çemberlitaş district of the Old City, the cistern was out of use and forgotten for centuries in the aftermath of the Conquest. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ottoman Arif Pasha had a big mansion built on top of it. Later on, in the 1950’s, the Eminönü Municipality building was constructed at the same site. The cistern was rediscovered only when, in 2010, the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality decided to demolish the Eminönü Municipality building. The cistern was unearthed and restored. The structures around the cistern were removed. A steel and glass entrance building was designed to provide direct access to the cistern.

Going down the steps from the entrance, you can instantly perceive that the Şerefiye or the Theodosius cistern is not as big as the Basilica nor the Philoxenus Cistern. Yet, with the numerous lights, it has an ambiance of its own. The dimensions of the cistern is said to be 45 metres by 25 metres. It is 9 metres high and supported by 32 columns. Similar to the one between the Basilica and the Philoxenus Cisterns, there is also said to be a connection between this cistern and the latter one as well.

This was the second time I had been to the Theodosius Cistern. I was already very much impressed the first time. The second time, with the beautiful carpets on display, I found it even more beautiful. I also thought that it was a superb choice as a venue for such an exhibition, because this land is one where a multitude of civilisations have left their traces. It has been a melting pot for the pagan, Hittite, Phrygian, Greek, Roman, Seljuk, Ottoman and countless other cultures. So, what would be better evidence to that than the beautiful Turkish carpets that are exhibited there now? As Mr. Mergen beautifully states, “Anatolian carpets are the common language and shared cultural heritage of all people who ever called Anatolia their homeland”…

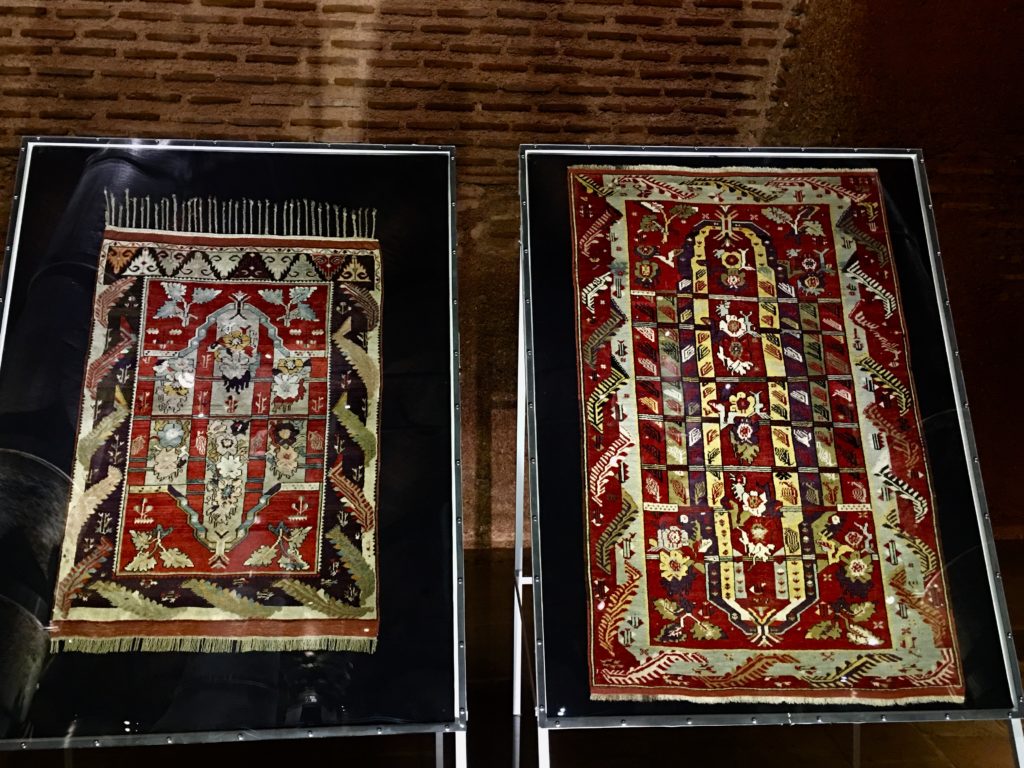

“Blooming Flowers in Caria” exhibition comprises 37 Milas carpets out of Mr. Mergen’s collection of 80 carpets from Milas, a town in South-West Turkey. The displayed carpets are dated to two main periods in time. The first period is mainly the time before the 20th century (1800-1880) while the other is between the 1930’s and 1980’s. Being a stellar town in the region of Caria in Antiquity, Milas (Mylasa at the time) carpets are a great testimony to the above-mentioned melting pot of cultures. No doubt each knot in a Milas carpet reflects a subconscious that includes both the great Herodotus of Halicarnassus and the nomadic culture of the Turkmen groups who much later brought their patterns, weaving habits and techniques to these lands from Central Asia. They had long ago learned how to shear the wool of their sheep, to get rid of the dirt that clung to it after which they turned the wool into yarns with a spindle. They also learned how to extract dyes from the natural resources in their habitat such as plant roots, insects and flowers. Using wooden frames to weave, they not only created the carpets and rugs that they needed in their daily lives but also poured their longings, their beliefs, sorrows and hopes with each knot as well.

has a renowned collection

There is no doubt that when Turkmens settled in Caria towards the end of the 13th century, they blended the cultural heritage that was already in these lands into their own ethnographic accumulation. Later on, during the Ottoman rule, when the State imposed population movements throughout the Empire for various reasons, Caria took its share. All of these factors created an influence that was clearly reflected in the architecture, handcrafts and above all the carpets of the region.

While some carpet experts and lovers strictly denounce the 19th century Anatolian carpets in view of the influence of the imperialist players (most of all the British and specifically the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers (OCM) company) on them, Mr. Mergen thinks otherwise. The former claim that, as a side effect of the İzmir-Aydın railway built by the British between 1858-1860, the Turkish art of carpet weaving was deformed. The use of natural dyes and handwoven yarn decreased dramatically (almost to extinction). The traditional patterns were replaced by those that pleased Western customers’ taste. In short, confined in the general rules of the game, the carpets became a commodity for global trade. Not refuting these actual facts, Mr. Mergen still thinks that the value of the carpets pertaining to this period should not be underestimated. He believes that, when carpets are considered as cultural objects that give us glimpses of the socio-cultural history of their time, then the carpets of the 19th century are full of hidden messages, facts and things to discover for us. Likewise, he believes that the hybrid carpets woven (by still using hand-spun yarns but mostly synthetic textile dyes while being loyal to traditional patterns) in the 1930’s and 1940’s that suddenly reappeared when Milas carpets were thought to be gone forever, are worthy of collecting and reflecting upon.

The exhibition is so full of beautiful carpets with wonderful patterns and colours that, none of these professional and academic discussions will come to your mind while you stroll among them. You will just get carried away with them, all the while thinking who wove them and what she was thinking about at the time. What her sorrows, joys or ambitions were about…

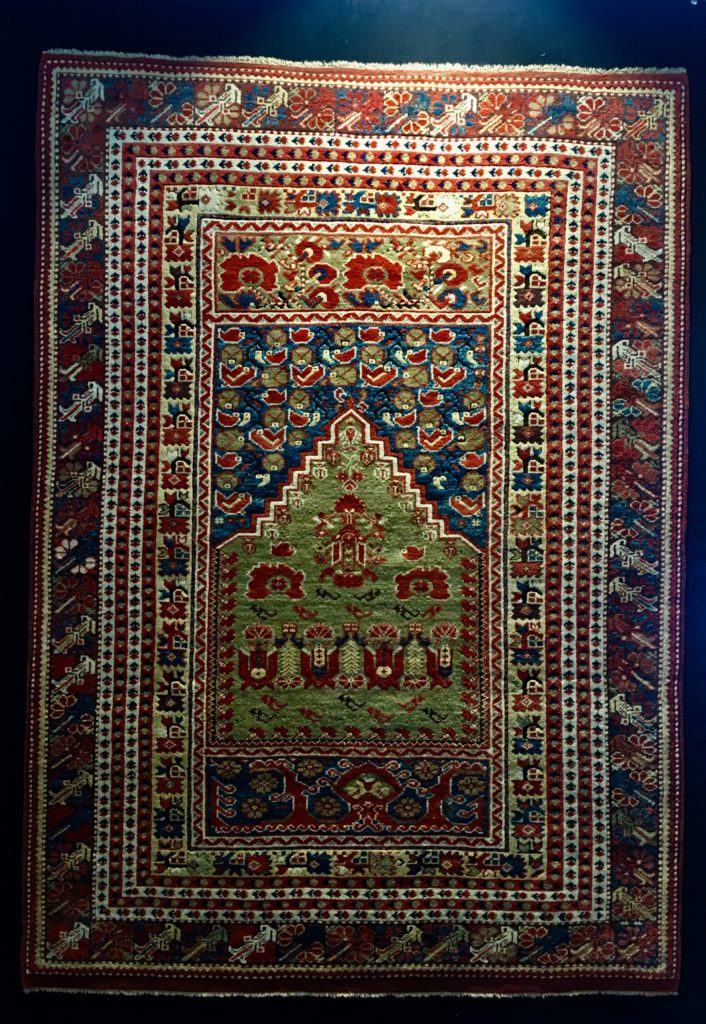

dated to circa 1850-1875

It is said that, Mr. Selçuk Mergen has an invaluable collection of precious antique carpets and that the ones in this exhibition are only a small part of it. All I can wish is that, one day he may display his admirable Sivas, Zara, Kula, Bergama, Yağcıbedir, Konya, Kırşehir and Mucur carpets and rugs for our mortal eyes to see in a private museum…