Istanbul is a city full of surprises and places to explore. Places that are in the midst of the commotion and yet, hidden at the same time. They are there for those who already know about them or those who can see. Shrouded by the general hubbub of this ancient and cosmopolitan city, they await people who like to seek the less known.

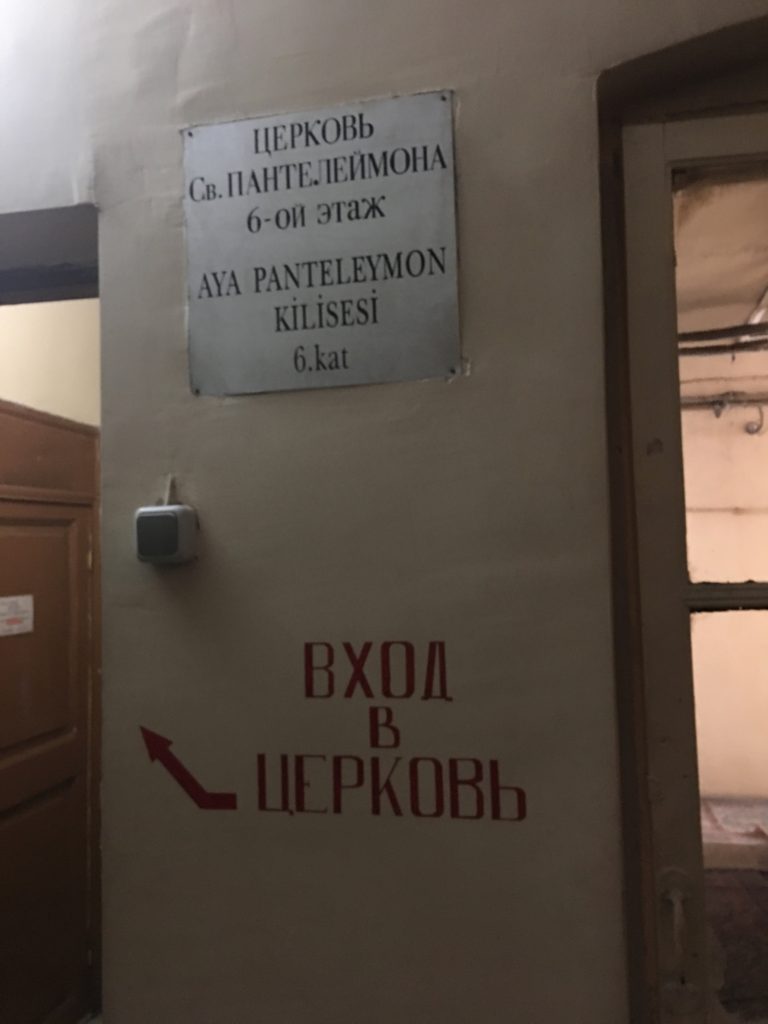

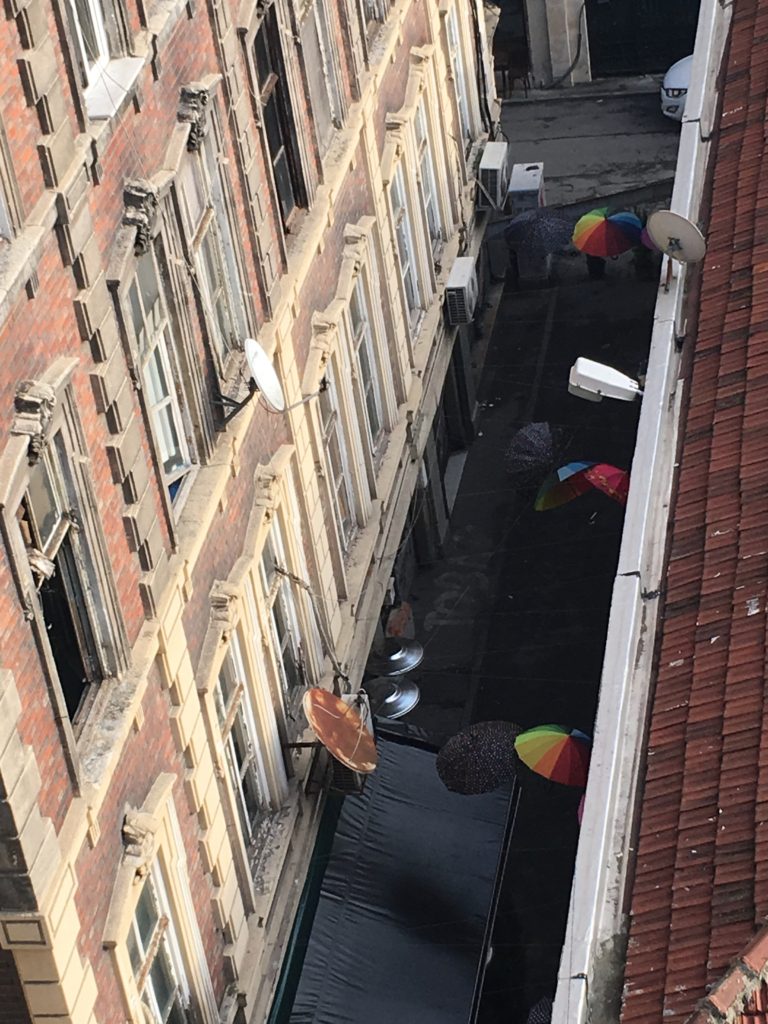

The Russian Aya Panteleymon Church is one of those concealed spots. Not because of the district or the street that it is located in but because it is in a least expected place. Aya Panteleymon is in the crowded district of Karaköy (by the Golden Horn), in a street (Hoca Tahsin St.) that is not all that deserted. In fact, it is quite busy. However, situated on the rooftop of a building, it is not exactly where you would look for a church. The small dome on top of the four-storeyed building is not visible from below. You would never think a church existed there unless you saw the sign at the entrance to the building. That is why, it is invisible to the majority of the locals and tourists who pass by.

Aya Panteleymon is one of the three Russian rooftop churches in the district. It was built in the 1870’s by Russians just like the Aya Ilia and Aya Andrea churches in the vicinity. The buildings themselves were designed to serve as inns for Russian pilgrims who were travelling to Mount Athos or Jerusalem. They would stop over in Istanbul to rest for a few days on their way to the holy destinations and back home to Russia. The churches on the top of the buildings were evidently built for the religious needs of these pilgrims.

Source: wowturkey.com

It was more than thirty years ago when I first went to Aya Panteleymon. We were in a special walking tour in the district and I remember being shocked when we entered the filthy and dark building. As our guide hadn’t told us anything about where we were going, I was wondering why we were climbing the stairs of this derelict building. It was a Sunday morning. Reaching the top of the stairs, we entered the Aya Panteleymon Church. Sunday Mass was barely over, and the smoke and smell of incense was still in the air…

Thirty years later, the building does not look any better from the outside. There is a scaffold on the façade which seems to have been put up to prevent any possible casualties that may occur due to falling plaster. I do hope that there will be an imminent renovation soon. Once inside, everything looked more promising. It was clean and well looked after. The place seemed to have been turned into a block of apartments. A very Russian looking young lady with a toddler seated in a stroller emerged from one of the doors. Could she be the descendant of the many White Russians who took refuge in Istanbul a century ago?

Times were hard following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Especially for the aristocrats and the supporters of the Tsar. The civil war between the Bolshevik Red Army and the pro-Tsarist White Army cost the lives of millions of people. The lives of thousands of others who fled the country were disrupted forever. The proximity of Istanbul made the city a destination for Russian aristocrats, civilians and members of the White Army for whom there was no future in Russia under the new regime…

The first wave of Russian immigrants came to Istanbul at the end of 1918 where they took refuge in the Russian Embassy. Some of them stayed in the buildings of the Aya Panteleymon, Aya Ilia and Aya Andrea churches. The number of immigrants increased in 1919 and reached a peak towards the end of 1920, when the commander of the White Army, Pyotr Vrangel, left Crimea on November 14, 1920, after a final defeat. Vrangel also came to Istanbul where he started living in a yacht. He also headed the Council meeting of the Russian Government in exile which was established in April 1921.

The almost 150,000 White Russian soldiers evacuated from Crimea were transferred to camps in Gallipoli and the Lemnos island. The civilians stayed in Istanbul. Among them were aristocrats of the highest ranks. Princes and princesses, barons and baronesses, generals and lower rank military officers were now in abundance in Istanbul. Some of them intended just to catch their breath before going to Paris or America. Others, could not go and stayed in Istanbul for the rest of their lives. They were given Turkish citizenship. Their descendants have been living in our city to this day. With their flawless Turkish, you would only recognise them by their names.

The Ottoman Empire itself was going through a great turmoil when the White Russians started seeking asylum in Istanbul. Maybe the greatest one in its history. It was the end of the First World War and Istanbul had been invaded by British, French, Italian and Greek troops on November 13, 1918. The Ottoman Empire was considered as defeated in spite of the Gallipoli victory of the Turks in 1915-1916, which proved the Dardanelles to be impassable for the Allied forces of Britain and France. At the time, the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill had planned to invade Istanbul and to link with the forces of the Russian Empire to wipe out the Ottomans for good. However, not only were the Allied Forces unable to cross the Dardanelle Strait but the Tsarist regime was overthrown in Russia in the meantime. Nevertheless, Istanbul was easily invaded two years later because the Empire was categorically treated as defeated due to its alliance with the Germans.

By the time of the final evacuation of Crimea and the last wave of immigration of the White Russians to Istanbul at the end of 1920, the War of Independence of Turkey was initiated under the leadership of Atatürk and the new government in Ankara. For strategic reasons, the new government considered a reconciliation with the Bolshevik Moscow government, a wise move. The start of the relations between the two governments unsettled some of the Russian refugees who sensed that the Ankara government was going to win the war against the invaders and a new regime was dawning in the country. So, another wave of Russians left Istanbul for Europe and America.

In spite of everything, around 50,000 White Russians lived in Istanbul for around three years. They brought a new flavour to the city’s cultural life and way of living. They liked to spend money and were keen on nightlife. Soon, there were many cafes, restaurants and nightclubs on and around the İstiklal Avenue in Pera/Beyoğlu (a high-end district of the time) that were run by Russians. The new Russian inhabitants of the city were also very fond of swimming. The sight of women with bathing costumes on the beaches of Istanbul caused quite a sensation at the beginning of the 1920’s.

Source: From the exhibition “Istanbul’s Seaside Leisure” (Pera Museum- 2018)

Life was not easy for all the White Russian refugees in Istanbul. Some of the nobility were confined to desolate lives and died in poverty. Money and pawned jewels ran out in time. The instinct of survival made them work in jobs that they would never have deigned to work at before. Furthermore, life was difficult and jobs were hard to find even for locals in those days. Our parents used to frequently mention doormen of hotels or nightclubs and street vendors of the time who were previously members of the Russian aristocracy. The more talented ones managed to live in better conditions.

There are two people who immediately come to my mind whenever the White Russians of Istanbul are mentioned. The first one is the lady who was the owner of the Ayaspaşa Russian Restaurant, in the vicinity of the Taksim Square. You would always see this old lady when you went to the restaurant until her death at the age of 90, in 1984. She was not very talkative but would always cordially welcome you. Her name was Judith Krischanovski, originally an Austro-Hungarian immigrant who was married to a White Russian. The couple opened the Ayaspaşa Restaurant in 1943. The restaurant is still serving good Russian, Austrian and Hungarian dishes with fine Russian vodka. It is said that, Madam Judith taught her headwaiter, who later took over the ownership of the restaurant, all the necessary secrets of her cuisine before she died. Forever grateful, he took care of her in her last years.

The second person was, Baroness von Clodt Jurgenburg, known in her later years in Turkey as Madam Taskin. The Baroness was married to one of Tsar Nikola’s officers, Baron Konstantin von Clodt Jurgenburg. When the Baron died in 1920 while fighting against the Red Army, the Baroness left her home country together with hundreds of thousands other Russians. After a sea voyage of 24 days, she reached Istanbul on November 24, 1920. She stayed with her General uncle and his family for a month and then, moved out. First, she worked as a maid in the American Hospital. Then, what was previously a hobby for her as an aristocratic lady, became her lifelong profession.

The Baroness left Russia when her husband died in 1920.

She had been playing the piano since she was seven years old. She started playing the piano in restaurants, cafes and cinemas. In the meantime, she remarried. Her second husband, Alexander Taskin, was also a musician and a Russian refugee. He was an aristocrat baptised by Tsar Alexander III. From then on, she became Madam Taskin. Together they continued to play music in the famous venues of the time. After the end of the War of Independence in Turkey, she became the first pianist of the Radio of Istanbul which was established in 1929. Once she also had the opportunity to play for the first president of the new Turkish Republic, Atatürk.

Source: facebook/Nermin Bezmen

Madam Taskin never left Istanbul. She stayed behind, even though many others, including her sister, left for Paris and the States. She spent the last decades of her life with her beloved Todori, a Greek Turkish citizen who was also a musician. They played together at a restaurant by the Bosphorus until her death in 1992, at the age of 90…

To share this post

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author