Polonezköy, which literally means “Polish village” in Turkish, is a cute little settlement on the outskirts of Istanbul, to the north of the city, on the Asian side. It is about 20 kilometers to the Black Sea and 15 kilometers to the Bosphorus. The Polish name of the village is Adampol, named after its founder Prince Adam Czartoryski. It is stated that, when Polish people first took refuge here in 1842, it took more than three hours on horseback to travel here from Beykoz by the shore of the Bosphorus. Going through the thick forest, travellers always faced the risk of attacks by bandits and wolves. Today, it is easily reached by car and has become one of the favourite destinations of Istanbulites for week-ends. Tourists who are staying longer than usual in Istanbul and who would like a break from sight-seeing, also find their way here, by first taking a ferry to Beykoz and then a bus from there to Polonezköy.

Locals mostly go to Polonezköy for Sunday breakfast or brunch. Some people stay all day long, ending the day with a barbecue under the trees. The village is a breathing outlet for tired Istanbulites who have to cope with the difficulties of the city during the week. There are numerous little cafes and restaurants in the village that also provide accommodation. If you want, you can stay there , take a long walk in the Polonezköy Natural Park and visit the few sights in the village. Once, this picturesque village was a hide away for lovers and illegitimate partners. Currently, with easy accessibility and the crowd on Saturdays and Sundays, it can hardly be called so in the week-ends. During the week it is always more quiet and enjoyable.

Puzzling as it may seem, it is best to briefly look into the historical relationship of Poland and the Ottoman Empire in order to understand why a group of Polish people set up a village close to Istanbul in the 19th century. The relationship between the two countries officially began in the year 1414 when the Polish King Wladyslaw Jegiello sent two ambassadors to the court of Sultan Mehmet I. Over the centuries, this first high level contact evolved into a relationship that covered trade, administrative collaboration and cultural influence. It is stated that until the 19th century, Poland sent fifty ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire. Some of them were also experts in Eastern languages. For example, it is recorded that the Polish ambassador Pawel Beone, who stayed in the Ottoman capital between 1572-1587, was able to speak fluently in Turkish with the Sultan. In return, the Ottoman Empire sent around twenty ambassadors to Poland in the same period. One of these ambassadors in the 16th century was Ibrahim Strasz who was in fact originally Polish and was working as a translator in the Ottoman Foreign Affairs.

The close historical relationship of the Kingdom of Poland and the Ottoman Empire does not imply that the two countries were always on peaceful terms. There were times of battles and invasions as well. The frontier that the two countries shared was the longest that existed between an Islamic and a Christian country at the time. It stretched from today’s Slovakia, Romania, Moldavia and the eastern Ukraine. Therefore, conflict was inevitable from time to time. For example, in 1444 the battle in Varna (currently a city in Bulgaria) ended with Ottoman victory and the death of Wladyslaw III, the King of Poland and Hungary. The Polish victory in the battle of Khotyn (in western Ukraine) in 1621 played a role in the killing of the young Sultan Osman II by the janissaries which was the very first time to happen in Ottoman history. Another drastic event for the Ottomans was in 1683 when King Jan Sobieski went to the aid of the Habsburgs, during the second siege of Vienna by the Ottoman army under the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa. However, this event turned out to be as drastic for Poland as it had been for the Ottomans. One hundred years after this event, instead of being grateful for stopping Ottoman penetration to Europe, Russia, Prussia and Austria decided to divide Polish land among themselves. As a result of this division, which took place in three phases in 1772, 1793 and 1795, Poland lost its independence for 150 years, until 1918. The Ottoman Empire was the only state at the time that did not accept this division. In fact, the notion of a free Poland was always kept alive in the Ottoman court during that period. For 150 years, the ambassador of Poland was always announced symbolically at the court ceremonies for the ambassadors of foreign countries. Each time, the announcement would be followed by the announcement: “The Polish ambassador is on his way my Sultan. He has been delayed due to the difficulties on the way”.

The abolishment of the Kingdom of Poland caused mass emigrations of Polish people to all over Europe, the New World and the Ottoman Empire. They were well received by the Ottoman State and their fine education and abilities enabled them to find employment in the Ottoman bureaucracy and military by which they contributed to the modernization processes of the time.

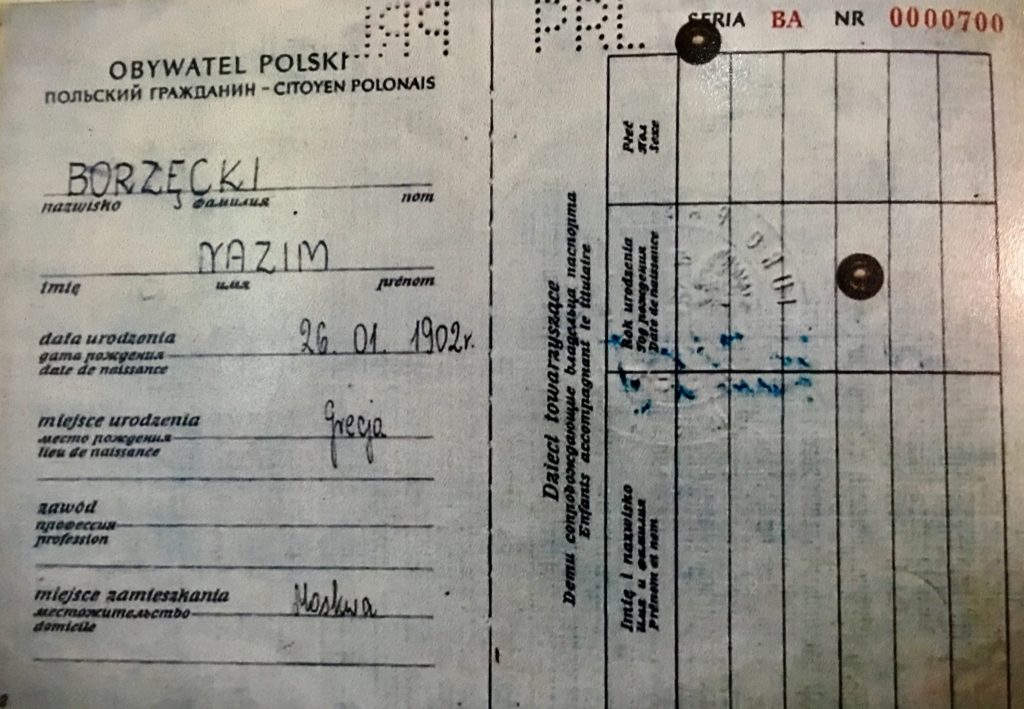

Following the division and invasion of Poland by Russia, Prussia and Austria in 1795, a National Polish Government in exile was established in Paris under the leadership of Prince Adam Czartoryski. In Prince Czartoryski’s view, Poland could regain its independence by fighting the Russians side by side with the Ottomans. Accordingly, in 1841 the Main Agency of the Polish Eastern Mission was founded in Istanbul. The Prince sent a renowned general and writer of the time, Michal Czajkowski to head this mission. In 1842, with the approval of the Prince, the General rented 5000 acres of land from the Lazarist priests of present day’s Saint Benoit High School in Istanbul. The Polish community in Istanbul and the wives of the soldiers who emigrated to Istanbul were in need of accommodation. The land was later bought by Prince Adam Czartoryski from the priests and the village that was established there was named as Adampol. Later, the village also acquired the Turkish name Polonezköy. In time, Polonezköy became a haven for the Polish patriots who took refuge in the Ottoman Empire.

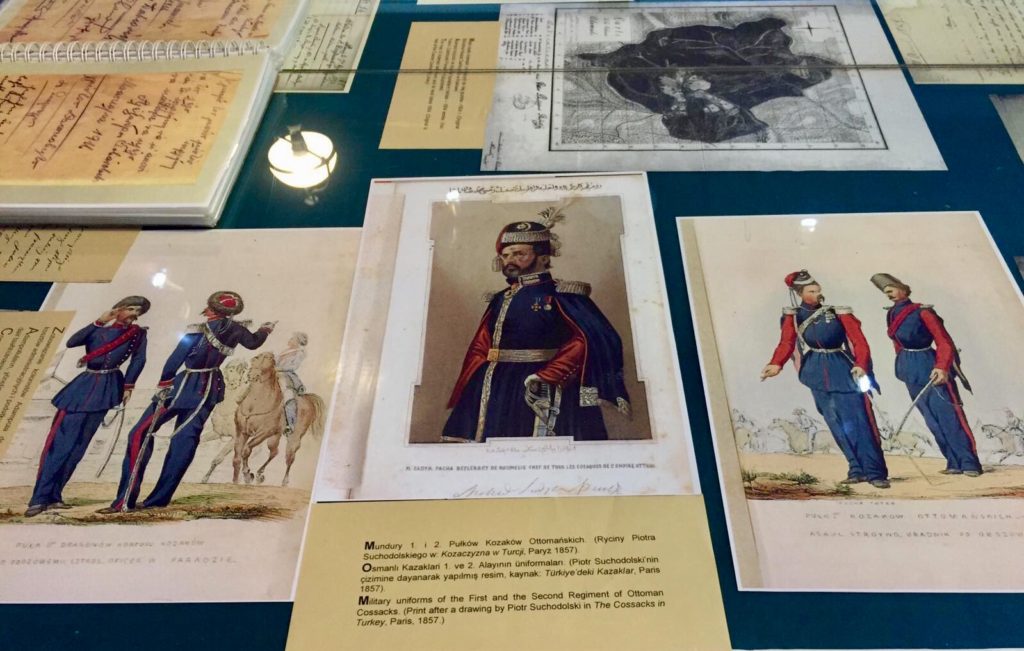

On the right and left, drawings of the uniforms of the Polish soldiers who fought as the Sultan’s Cossacks Division during the Crimean War

(The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy)

(The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy)

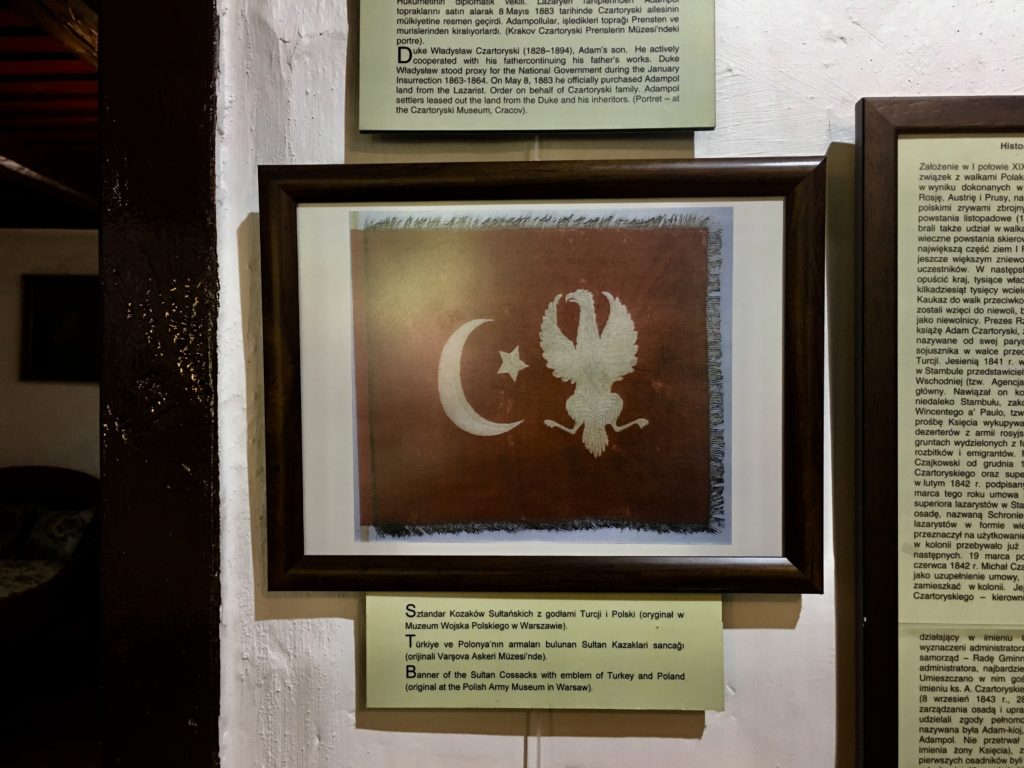

General Czajkowski was later to convert to Islam and take the name Mehmet Sadık Pasha (1804-1886). He organized and led the Sultan’s Cossacks Division, a cavalry regiment in the Ottoman army, during the Crimean War (1853-1856) that fought against the Russians. Polish soldiers fought for the Ottoman Sultan against Russians on every front from the Balkans to the Caucasus. The war between the Turks and the Russians was regarded as an opportunity for the Polish to take their country back. That is why 8000 Polish patriots fought side by side with the Ottomans against the Russians in this war. The great Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz was also sent to Istanbul by the Prince to raise the morale of the Polish soldiers. Unfortunately, he died here of cholera. After the war, Sultan Abdülmecit honoured and rewarded these soldiers and granted tax exemption to those who were to live in Adampol/Polonezköy.

(The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy)

When Poland regained independence in 1918, some of Polonezköy’s inhabitants left for Poland. In time, Muslim families also started settling in the village. It is stated that currently there are around 700 people living here out of which 90 are Polish. Most of them are fluent in Polish. The community has been keeping their traditions and living peacefully without being assimilated. I must say that their command of the Turkish language is also excellent and without any flaw in their pronunciation. You can only understand their origins by their Polish names.

The good relationship between the two nations continued throughout the Second World War and during the Cold War, even though the two countries were part of opposing blocs. Polonezköy is now the symbol of the friendship between the Turkish and Polish nations. The village was visited by many famous people since its foundation. Among them are Atatürk, Franz Listz, Gustave Flaubert, Pierre Loti, Pope Jean XXIII., the Polish Presidents Lech Walesa, Aleksander Kwasniewski, Kaczynski and Komorowski.

As I have previously mentioned, Istanbulites usually go to Polonezköy on week-ends for breakfast. Breakfast (kahvaltı) is still an important meal for Turkish people, even though the hard living and working conditions, augmented by traffic congestions, in big cities have now diminished the possibility of having a proper breakfast at home. However, almost everyone tries to make up for this situation during the week-ends. The tradition is kept alive with big breakfasts on Sundays, either at home or in numerous cafes or restaurants all over the city. I will be writing in more detail about the Turkish breakfast tradition in a future post.

The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy and the Czestochowa Virgin Mary and Saint August Czartoryski Church are two sights in the village that clearly mark the Polish ancestry. The former of these was the house of Zofia Ryzy who was the daughter of one of the first settlers in the village. Just like her father, she collected everything she could get hold of related to the history and origins of Adampol/Polonezköy. Going from one room to the other in this small house, you can catch a glimpse of the difficulties the first settlers faced, how they lived, their fighting against the Russians as a part of the Ottoman army and much more. Zofia Ryzy died in 1986 and her house was turned into a museum in 1992, as a part of the 150th year commemorations of Adampol/Polonezköy. Zofia Ryzy used to say, “We are in an extraordinary situation. Poland is our fatherland, but Adampol on the Bosporus is like Poland with all its traditions on the Turkish soil”. All her life, she tried to preserve the Polish culture in the village by teaching the language and the history of their homeland. Her descendants still live in the village and own a boarding house and restaurant.

Unfortunately, the church of the village was closed when I last visited Polonezköy a couple of weeks ago. It was probably open for the Sunday Mass which we missed. Construction of this church started in 1914 following a decree by Sultan Mehmet Reşat V. It has a beautiful and well-kept garden. The cemetery is also stated as worth visiting.

(The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy)

(The House of Memory of Zofia Ryzy)

Taking a stroll in the village was quite a challenge on that sunny Sunday. Road sides were full of cars that left no walking space for pedestrians while careless drivers dashed by at high speed. Almost all cafes were packed with people who had made reservations days ago. I definitely recommend going to Polonezköy during the week instead of on week-ends. It was evident that things had changed a lot in this once quiet refuge for Polish people. Looking at the beautiful old Polish style houses on the green meadows and in the beautiful gardens, I could only wish for the best for Polonezköy in the future. I do hope that the tradition and the culture will survive, even if with difficulty, for generations to come.