I really can’t remember how many times I’ve been to Hagia Sophia. I believe at least half a dozen times. This temple of “Holy Wisdom” has impressed me with its divine beauty each and every time I’ve been there. Yet, visiting it by night was something else. Almost magical…

The experience of visiting Hagia Sophia is probably too personal to generalise. The structure itself, apart from the mosaics and other ornaments, is captivating by its very immensity. The impression is even more enchanting by night. Even though at night you cannot see every corner and nook that you could during the day, the low lights inside create an entrancing atmosphere. It gives you a feeling of going back in time to the Byzantine days of oil lamps. The Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism has recently allowed admission to several historic sites at night in Istanbul and Hagia Sophia is one of them. However, visits are only possible if you participate in the tours of a limited number of travel agencies with special permission for pre-determined dates. In my opinion, a first visit should definitely be in broad daylight if you want to fully appreciate this monument. The night visit could be an extra indulgence if you have the time and the money.

The immaculate and breath-taking Hagia Sophia has been adorning the skyline of this ancient city of Istanbul for almost fifteen centuries. That means one thousand five hundred years. Easy to say, but hard to imagine… It has survived earthquakes, loots, conquests and outlived numerous Byzantine emperors and Ottoman Sultans. It put up with the fierce attack of the Fourth Crusade headed by the Venetian Dodge Dandolo and, together with the whole city, witnessed one of the most wicked plunders in history. However, there it still stands, with all its magnificence while all those historical figures have long been reduced to dust. First built as a cathedral, then turned into an imperial mosque, it has been a museum since 1935. Currently, it is one of the three most visited historical sites in Turkey. Hopefully, it will be there till eternity as a heritage of all mankind…

The Hagia Sophia that we see today, is the third church with the same name that stands at that location. The first of these churches was inaugurated in 360 A.D., during the reign of Constantius, who was the son of Constantine the Great. It was set on fire by mobs during a riot in 404 A.D. and the reconstruction took a long time. The second Hagia Sophia was completed in 415 A.D. under the reign of Emperor Theodosius II. Unfortunately, this church was also burnt down during the Nika Revolt on January 15th, 532. The revolt initially started in the Hippodrome as a riot between the Green and the Blue chariot teams but soon turned against Emperor Justinian I who had become increasingly unpopular due to his heavy tax policy.

Justinian I, who reigned between 527-565 A.D., was an ambitious ruler. First and foremost, he tried to regain Roman territory in Italy. Thanks to this determination, we can now see the most beautiful examples of Byzantine architecture and art (such as the Basilica di San Vitale and Basilica di Sant’Apollinare in Classe) in Ravenna, Italy. However, Justinian’s dream of bringing back the glorious days of the empire, together with his extensive building projects and the ongoing war with the Persians required him to continuously increase the taxes. Meanwhile, he was also intent on ending corruption. All of these factors augmented the feeling of resentment in several classes of the society. During the Nika Revolt, riots continued for several days. Constantinople was in flames and Hagia Sophia took its share. The city was in a devastated state when the revolt was finally crushed.

According to the chronicler Procopius (500-565 A.D.), “God allowed the mob to commit this sacrilege, knowing how great the beauty of this church would be when restored”. Today, one cannot but agree with Procopius that the beauty of this last Hagia Sophia is indeed great. Justinian initiated the rebuilding of the church immediately after peace and order was restored in the city. It was to be a totally different and much bigger church. Skilled men from all over the country were brought to the capital and the expenses for the construction were never to be an issue. It took five years to build Hagia Sophia and it was formally dedicated by Justinian on December 26th , 537.

From the outside, the building is colossal with its huge dome, semi-domes and buttresses. To me, the minarets at the corners are also in great harmony with this stupendous church. The red brick minaret on the right (when you face Hagia Sohia with your back to the Blue Mosque) was commissioned by Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror (Fatih Sultan Mehmet), the one behind it by his son Sultan Beyazıt II and the two minarets on the left by Sultan Murat III. These last two are the work of art of the great Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan who also built the great Süleymaniye Mosque in the 16th century.

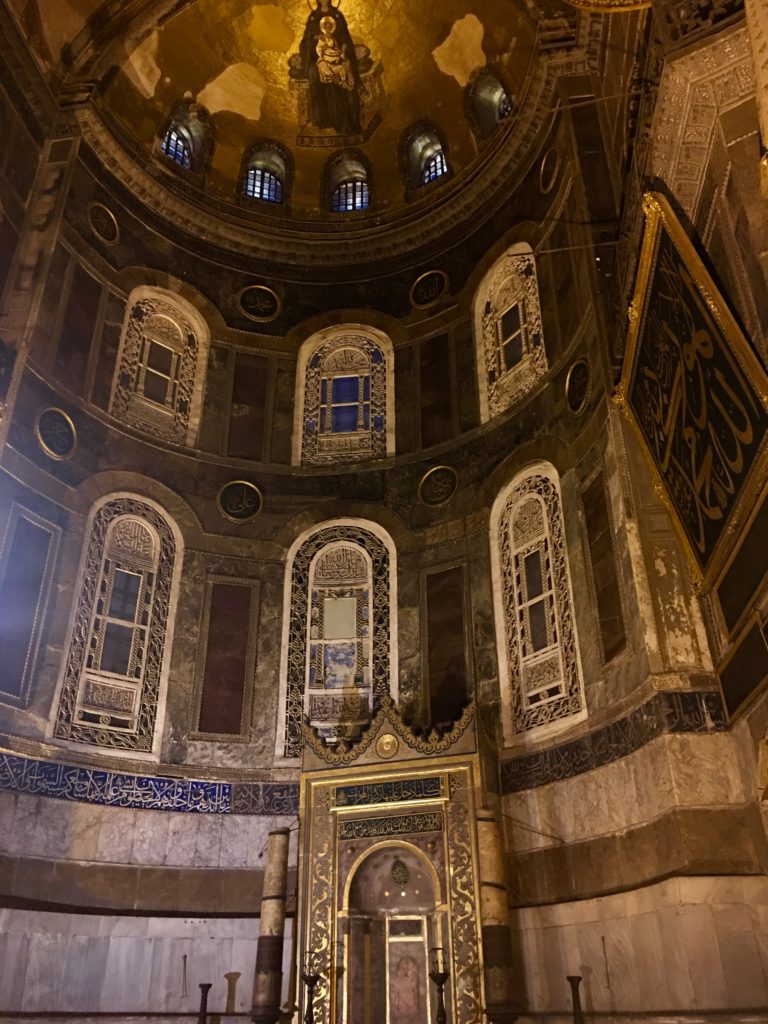

When you enter the nave of Hagia Sophia through the Imperial Gate, you cannot help your gaze from wandering to the dome hovering above you at a height of 56 metres above the floor. The spaciousness almost immediately reminds us of how small we human beings and our worries are compared with the universe that this grand dome possibly symbolises. First, you try to take everything in at once. Then you start focusing on the numerous details…

The immense proportions of Hagia Sophia at once triggers the question of how could man possibly create something like this 15 centuries ago. I keep on asking this to myself every time I go there. Given the conditions of the time, it seems like a miracle. Well, evidently it was not. Both of the architects who were in charge were also distinguished scientists of the era. The head architect Anthemius of Tralles was one of the renowned mathematicians and physicists of the age and his assistant Isidorus of Miletus was the greatest geometer of late antiquity. Isidorus took over the project when Anthemius died shortly after the start of the construction.

Hagia Sophia was barely a year old when it was hit by an earthquake. The damage was severe with the collapse of the eastern arch and semi-dome and the eastern part of the great dome. The altar was also crushed by the collapse. However, Justinian was not discouraged and once again he made sure that repairs started immediately. This time, he entrusted the restoration to the nephew of Isidorus of Miletus. The remedy that Isidorus the Younger found was to make the dome higher than before, which seems to have worked out since the structure survived the two later partial collapses in its history. The dome of Hagia Sophia is slightly elliptical. The east-west diameter is 31 metres while the north-south diameter is 33 metres.

Hagia Sophia went through several restorations during Byzantine and Ottoman periods. Nevertheless, the building that we visit today is still basically the same as it was during Justinian’s time. The major additions to the original building were the huge buttresses that support the building from the north and south sides. These were initially built during the reign of Emperor Andronicus Palaeologus, in 1317, to prevent an imminent collapse. They were restored and fortified in Ottoman times as well. The last extensive restoration of Hagia Sophia in the Ottoman period was commissioned by Sultan Abdülmecit to the Swiss-Italian architect brothers Fossati, in the years 1847-1849. The building has gone through several restorations and has been under continuous surveillance since it became a museum after the declaration of the Turkish Republic. In fact, many people complain because there is almost always a high scaffold inside which blocks different frescos or mosaics on the ceiling, at different times. However, archaeologists insist that this is a requirement due to the age of the building and that it must be taken care of at all times. As a matter of fact, I think I only saw Hagia Sophia twice without the scaffolding in my lifetime. Lastly, it was removed in 2010 when Istanbul was declared the Cultural Capital of Europe but was reconstructed shortly afterwards.

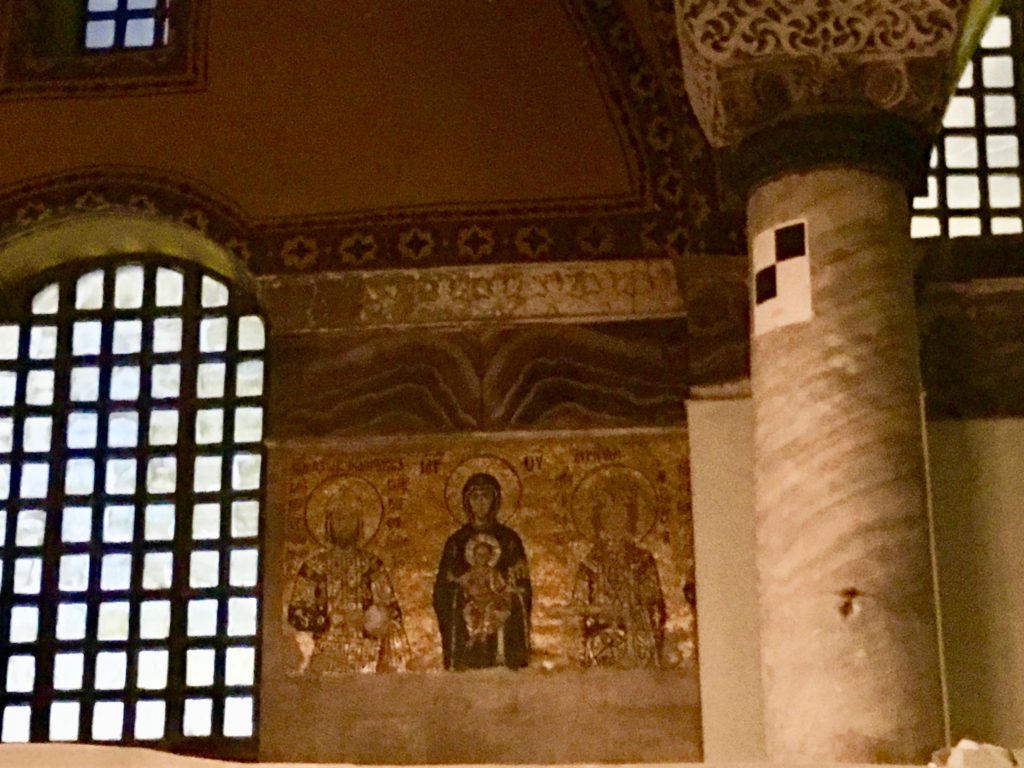

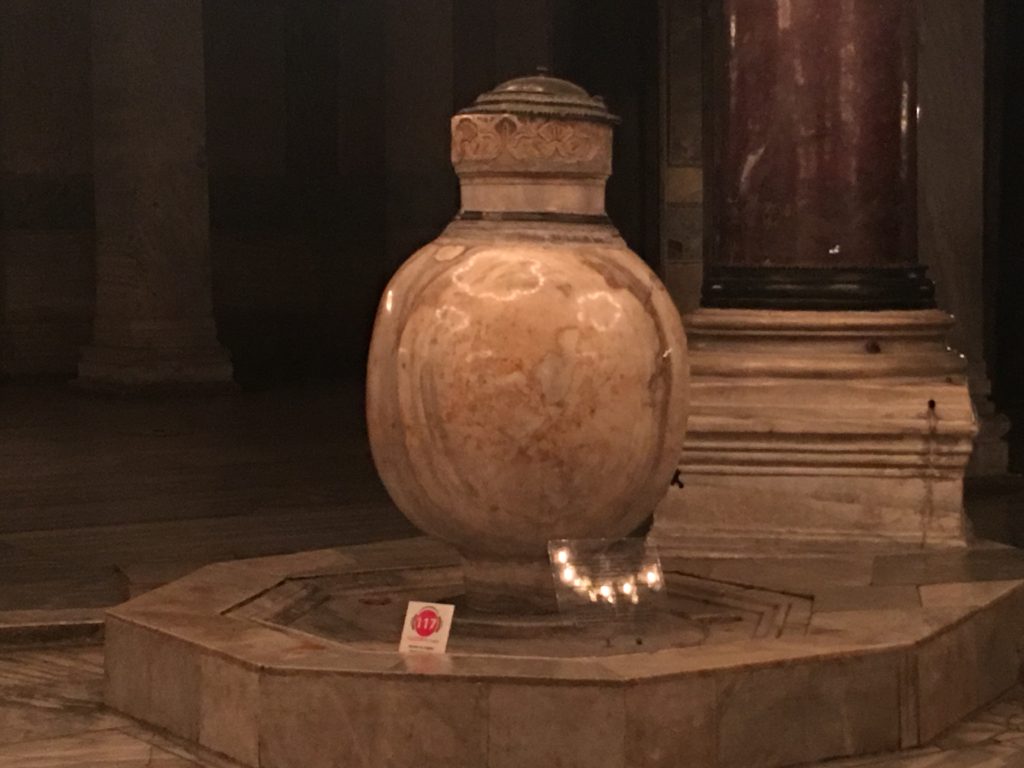

It is believed that in Justinian’s time there were no figural mosaics inside the basilica. However, the walls and ceilings were covered with gold coloured mosaics that gave a magical and affluent effect with the rays of sun coming through the windows. The geometrical and floral figures in different colours, in addition to the little crosses on the crowns of the vaults were also the work of that period. Most of these still remain inside the basilica. Whatever figural mosaics that may have been done after Justinian’s time were definitely destroyed during the dark iconoclastic period between 729-843. Therefore, the beautiful figural mosaics that we see today are mainly from the second half of the 9th century and the 10th century. The VI. Leon Mosaic above the Emperor Gate, The Offering Mosaic above the doorway in the Vestibule of the Warriors, the Virgin Mary mosaic in the apse are all dated to this period. There are other beautiful mosaics in the galleries upstairs which should not be missed. The galleries are accessed by an inclined labyrinth that is entered at the northern end of the narthex on the ground floor. The stones on the ground of the labyrinth are very slippery. Probably due to centuries of use. If you think it is taking too long to go up, bear in mind that you are climbing a height equivalent to the height of a five-storey building.

Looking down on to the nave of Hagia Sophia from upstairs is a stunning experience. Stand next to the balustrade right in the middle of the balcony, facing the apse. This is the point from where you can take in the whole magnificence of the building. This spot, which is marked by a round disc of green marble, is where the throne of the Empress was put. She and her ladies-in-waiting would follow the ceremonies and masses from here while the Emperor sat on his throne downstairs. Initially, the entire upper section was used as gynaecium or women’s quarters. However, later some parts of the galleries were reserved for other purposes. The upper floor was also very conveniently used as the women’s section when the building was turned into a mosque.

The Deisis Composition, the Komnenos Mosaic and the Zoe Mosaic are among the beautiful mosaics upstairs. Others, such as the mosaics in the Priest Rooms were not open to the public. I must also say that, when you visit Hagia Sophia by night, you risk not seeing some of the mosaics properly due to the low lights.

The mosaics are not the only treasures of the galleries upstairs. There, you can also see the tomb of the Dodge of Venice, Henricus Dandolo, who was the leader of the Fourth Crusade. He was responsible for the most destructive looting Constantinople ever went through in history (1204). The famous four horses (Quadriga) of the San Marco Basilica in Venice are only one of the many treasures that were taken to Venice at the time. The Latin reign of the city lasted until 1261 but, Dandolo died in 1205 and was buried in Hagia Sophia.

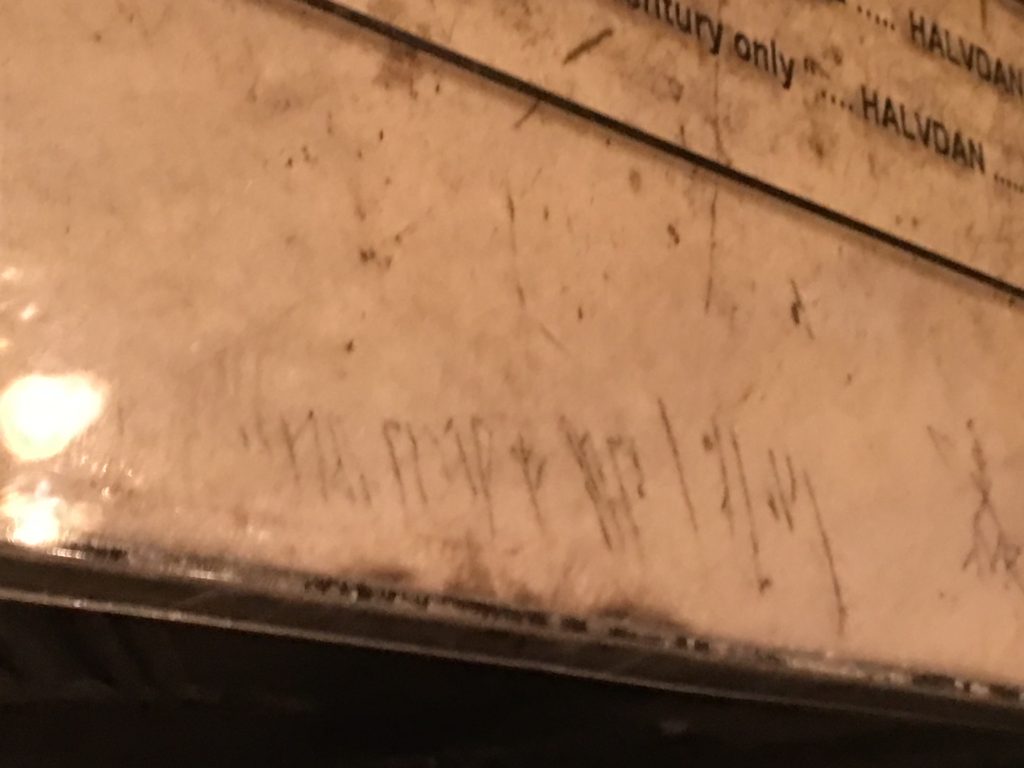

The Viking inscription on the marble bannister of the south gallery is another interesting point of attraction. This writing, dated to the 9th century, is said to belong to a Viking mercenary soldier in the Emperor’s army. The inscription, “Halvdan was here”, probably belonged to one of the Viking group of soldiers who were named as Varangian and were part of the Imperial Guards. These brave and strong men fought for the Emperor on every front of the empire for around 200 years.

Inscription of a Viking soldier in the Emperor’s army (9th century)

Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror knew about Hagia Sophia long before he conquered the city. He was a great admirer of Byzantine art and literature. Born from a mother with Greek and Christian origins, today we know that he was fluent in Greek. His personal copies of the Iliad and Odyssey in Greek are currently kept in the library of the Topkapı Palace.

One of the rectangular columns in the northwest part of the building is partially copper plated and has a hole in the middle. This column has been related with various legends, both in Byzantine and in Ottoman times. Today, people put their thumb inside and try to rotate it 360 degrees to make a wish come true. The moisture inside is said to be due to the cistern under the basilica.

It is stated that, when he entered the city in the late afternoon of the same day of the conquest, May 29th, 1453, he rode slowly on his white horse through the streets of the city until he reached Hagia Sophia. He dismounted at the door of the basilica, bent down to take a handful of earth from the ground and sprinkled it over his turban as an act of humility before God. Upon entering the basilica, he did not restrain himself from expressing his admiration for the architecture, the mosaics and the artefacts. Having walked around for a while, he ordered the removal of the dead bodies inside. Afterwards, he and the Muslim congregation with him stood in prayer here for the first time after the conquest of Istanbul. Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror thoroughly repaired Hagia Sophia. Because figurative representation in mosques is prohibited in Islam, the mosaics and frescos were covered either with wooden lids or plaster but were not destroyed. Some of these mosaics were rediscovered when the basilica became a museum in 1933. The name of Hagia Sophia was never changed and remained as the Hagia Sophia Mosque during Ottoman times. Considered as one of the most important imperial mosques, it was always looked after by the following Sultans. Thanks to them, we have not been deprived of this ancient beauty of all times…

__________________________________

Note: The different dates that are given in the text for the opening of the Hagia Sophia Museum is due to the fact that, it was closed to the public as a mosque in 1931 when restorations started. The official opening of the museum was in 1935.