April is the month of tulips in Istanbul. There are tulips of all colours galore on road sides and parks all over the city. However, two parks are the main points of attraction. The Emirgan Park on the European side and the Göztepe 60. Yıl Park on the Asian side. Tulips have historically been a very important element in Turkish (both Selcuk and Ottoman) art and literature. Tulip motifs can be seen on the most beautiful tiles in mosques, palaces and mausoleums, on miniatures, embroideries, fabrics and in the creations of the Turkish art of marbling (ebru).

This beautiful flower which was once so much loved, both by Turkish rulers and their subjects, was almost forgotten by the 19th century. After previously being so precious and sought after, it was quite astonishing that tulips should phase out into oblivion. They were once the symbol of a period of time in Ottoman history, that was later to be named as the Tulip Era. Perhaps this aversion from tulips was due to the dramatic way in which the era ended. Tulips were neither planted nor frequently seen in gardens or parks anymore. Meanwhile, tulips were becoming ever so popular in the West, especially in Holland. It was only fourteen years ago that the disloyalty of Turks to tulips has come to an end. In 2005, the Municipality of Istanbul inaugurated the Tulip Festival of Istanbul by planting millions of tulip bulbs around the city. Since then, every spring Istanbulites have eagerly been waiting for the tulips to bloom.

Tulips are originally from Central Asia and in reality, they are wild flowers. Tulips were not known by the Romans nor by the Byzantines. They were brought to Anatolia by the Turks as of the 11th century. It is stated that, currently there are about fifteen main types in Anatolia and more than five thousand varieties of tulips, including the experimentally produced ones, in the world. Tulip motifs started to appear on Selcuk monuments, in books and artefacts starting from the 13th century.

Photo credit to Caner Cangül

Tulips found their way to Holland in the 16th century. It is believed that the ambassador of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Istanbul, Ogier Gisleen van Busbeke (Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq in French), during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, was the person who took some tulip bulbs with him to Vienna at the end of his stay. He later gave some of the bulbs to his friend, Charles de l’Écluse, the Flemish botanist and prefect of the Emperor’s gardens in Vienna. When Charles de l’Écluse later moved to Leiden in Holland, he took some of the bulbs with him and continued with his experiments and breeding there.

The original type of tulips that were brought from Istanbul to Europe were later on named as tulipa turcarum by botanists. The word tulip is thought to have been generated from the word turban, a headgear that was worn in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. In time, Charles de l’Écluse’s experiments and the artificial varieties that he bred became so popular that they became a status symbol in Holland. Eventually, the “Tulip Mania” got so out of control that, a single tulip bulb became more expensive than a diamond. Wealthy people competed with each other in making others jealous of their tulip gardens, all the while investing in more expensive bulbs. Prices skyrocketed until one day in 1637 the market crashed, creating one of the historical commercial disasters of all times.

The Emirgan Park

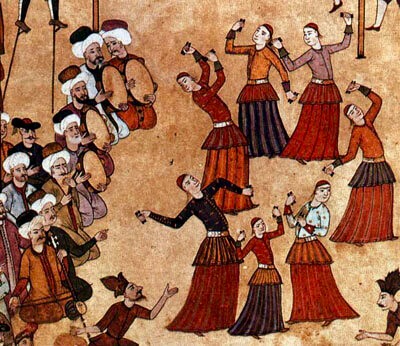

While Europeans and the Dutch were interested in the commercial value of tulips, Ottomans regarded it as a beautiful, heavenly flower. Almost sacred. This was all the more supported by the Ebced (Chronogram) representation of the word tulip in Turkish. Chronogram or time-writing (Ebced) was one of the most popular and important literary forms used in Ottoman literature. This form of writing, which was acquired from Persian literature, was used to record the dates of important events such as enthronements, military campaigns, victories, defeats, births, deaths, circumcisions, fires, earthquakes etc. They were also incorporated within inscriptions on buildings (such as palaces, fountains and public baths) to mark their construction or renovation dates. According to Ebced, each Arabic letter had a number assigned to it. The Ebced value of the word Allah (God) and Lale (tulip) both added up to 66, making tulips a sacred flower for the Ottomans. In this way, it became widely used allegorically on the tiles in mosques, in miniatures, poems and stories.

Although he was not the only Sultan who loved tulips, Sultan Ahmed III (1673-1736) was the most prominent among them for his special affection for this flower. So much that, the twelve years between 1718 and 1730 during his reign was later named as the Tulip Era, in the 20th century by the famous Turkish poet Yahya Kemal. The period has been called accordingly ever since.

Sultan Ahmed III was confined to the “cage” until he was 33 years old while his uncle and two brothers ruled the country, one after the other. The term cage is not to be taken literally. As I had previously mentioned in one of my posts, according to a law made by Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (Fatih Sultan Mehmet), Ottoman Sultans had their male siblings killed as soon as they were enthroned. The reason for this law was the previous long periods of civil war in the Ottoman history. The uprisings and claims to the throne (often backed by foreign countries) by the Princes (Şehzades) caused long periods of strife and fighting. The most drastic of these was among the sons of Bayazid I and lasted more than a decade. The law was made to prevent this struggle because it harmed the State. It was practiced for nearly 200 years, until the reign (1603-1617) of Sultan Ahmed I, who resisted killing his brothers. Sultan Ahmed I refused to apply this law because, as a child, he had seen the 19 coffins that belonged to his uncles, all lined up in the courtyard of the Topkapı Palace, when his father ascended the throne. He was devastated and later on called his late father a murderer when he himself ascended the throne. His father, Sultan Mehmed III had not even spared his a few days old brothers.

After the abandonment of the law, Princes who were in line, including the immediate heir, were kept in special apartments in the palace instead of being killed. The term cage is probably due to their confined lives behind barred windows and locked doors. This was almost like an imprisonment and could be decades long. Some Sultans stayed in the cage for 30 to 40 years before ascending the throne. This clearly affected the mental health of some of them. They had to live in confinement with one or two concubines to serve them and were not allowed to have children because that would create even more complications in terms of rivalry to the throne. Some sources claim they were not even allowed to have sex but that does not seem very realistic. However, if any of their concubines became pregnant by any chance, an abortion was the inescapable consequence.

When Sultan Ahmed III moved to Istanbul from Edirne, where his enthronement took place, the capital city of the empire was almost in ruins. The Ottoman dynasty had been living in Edirne (the capital city before the conquest of Istanbul) for nearly 50 years because the Sultans enjoyed hunting in the area and were fond of the palace there. Neither was the city safe, due to the attempted uprisings, thefts and strife in the streets. During the early years of his reign, the young Sultan had to deal with the wars with Venice, Austria and Russia. However, after the Treaty of Passarowitz (in today’s Serbia), with Venice and Austria, on July 21st, 1718, a long period of peace followed. During this period, Istanbul underwent a serious reconstruction. Palaces, pavilions, parks and gardens were built in previously empty areas along the Bosphorus, in addition to the renovated ones in the Old City. The parks and gardens were adorned with tulips of the rarest kind. Tulips became the favourite flower of the rich. Waterways, aqueducts and fountains were built throughout the city. Two of these (one in front of the Topkapı Palace and the other in Üsküdar on the Asian side) were commissioned by the Sultan himself and are named after him.

The Tulip Era was a period when the Ottomans tried to catch up with the Western World of the time. The inauguration of the first official printing house, the formation of the first fire brigade (Tulumbacılar Ocağı) in Istanbul, the establishment of paper, glass and ceramics factories and the use of small-pox vaccination for the first time were all important steps toward this goal. It was also during this period that the Ottomans ever sent an ambassador to Europe. Çelebi Mehmet Efendi was sent to Paris by the Sultan to represent the Ottoman State. Several libraries (the most beautiful one being the Sultan Ahmed III Library inside the Topkapı Palace) were also built and books in foreign languages were translated at this time.

Despite the above-mentioned improvements, the extravagant day and night parties in the tulip gardens and the expensive public celebrations, in addition to the high level of inflation and unemployment, caused considerable bitterness among the ordinary people. This was the first time the palace extravagance and extremity was being exposed outside the palace walls. Naturally, the religious leaders also disapproved this luxurious and expensive life style of the ruling class. Furthermore, the Sultan’s reluctance for a new military campaign enraged the Janissaries whose main source of income was looting conquered lands. In the end, in 1730, Sultan Ahmed III was overthrown with an uprising led by a Janissary commander, Patrona Halil. The chaos continued for three days but Sultan Ahmed III was not killed. He was shut up into the “cage” with his sons where he stayed until his death in 1736. His cousin, Sultan Mahmud I continued with the reconstructions and improvements he initiated but the Tulip Era and the popularity of its main character, the tulip flower, had come to an end…

Built in 1728, it fully reflects the architectural characteristics of the Tulip Era