Water supply was always a crucial problem to solve for Istanbul. It still is but, thanks to today’s technology, the solution is relatively easy if not inexpensive. On the other hand, solutions to this problem have been brooded on since antiquity by the rulers of this ancient city and the remains of those remedies continue to fascinate us now…

Byzantium (name of the city at the time) became a Roman city in 196 A.D. after the attack of the Roman emperor Septimus Severus. In 330 A.D. the city took the official name of Nova Roma (New Rome) but in everyday language it was Constantinopolis (city of Constantine) from the beginning.

Similar to Rome in Italy, Constantinopolis spread over seven hills. Six of these hills are along the Golden Horn while the seventh one is within today’s Samatya and Çapa-Cerrahpaşa areas. It must be noted that, contrary to what even a majority of locals mistakenly know, all of these hills are in the Old City part of Istanbul. I believe this error is because the rest of the city also lies on numerous hills.

The Romans, and the East Romans (330-1453 A.D.) after them, built an impressive and very effective water system consisting of channels, aqueducts, distribution chambers, fountains, water levels, wells and cisterns to solve the water problem. While doing this, they fully took the topography of the city into consideration, taking advantage of the hills and overcoming the disadvantages of valleys with elaborate engineering techniques. Some of these were repaired and used by the Ottomans after the conquest of the city in 1453, in addition to the aqueducts, dams, reservoirs, and fountains built by the order of the Sultans.

I believe, the Basilica Cistern or the Underground Palace (Yerebatan Sarayı in Turkish) near Hagia Sophia is on the regular itinerary of most tourists who come to Istanbul. It is the biggest and most impressive cistern of the city. Binbirdirek (A Thousand and One Columns) or the recently renovated Theodosius cisterns can also be visited. However, they are not the only ones. There are countless others under the buildings in the Old City. Some of these are under the hotels and shops in the region. Some have been renovated while others are waiting desperately to be taken care of because they have been emptied and used as warehouses during and after the Ottoman era.

Not all cisterns in Istanbul were initially built for water collection. Some are ordinary basements that were later turned into cisterns. These kinds of cisterns can be found under monasteries and churches. It is said that there is such a (12 metre deep) cistern under Hagia Sofia as well.

In this post, in addition to the three cisterns mentioned above, I will be taking you to some less known cisterns that I had the opportunity to see a few months ago. These were among many others that were covered during the tour I participated in. Some were under hotels while others were under shops and places that I would never have imagined contained a cistern. They were discovered during the construction of the contemporary buildings above and were renovated. All of them were within the Old City boundaries of Istanbul. However, it is known that cisterns also exist at various places across the Golden Horn, along the Bosphorus and on the Asian side of the city.

The Basilica or the Underground Palace Cistern (as it has been called since the Ottomans) is currently the biggest known cistern in Istanbul. It was named as the Basilica Cistern in the Byzantine era because, at the time, it lay beneath the Stoa Basilica on the First Hill. The Basilica Cistern was built by emperor Justinian during his attempt to rebuild Constantinople after the Nika Revolt in 532 A.D. In Byzantine Istanbul, this beautiful cistern was used to supply water primarily to the Grand Palace and the other major buildings on the First Hill. It was later used for the irrigation of the gardens of the Ottoman Imperial Palace, Topkapı. However, quite surprisingly, the cistern was somehow forgotten for a period of time until it was rediscovered in 1545. On the other hand, this oblivion had only been from the part of the aristocracy and the upper classes because, ordinary people in the neighbourhood had continued to draw buckets of water from this cistern through the holes they made in their basement floors. They even caught fish through those holes.

The Underground Palace Cistern is not only very large, but it is very beautiful as well. Previously, you were only able to look onto the cistern from a platform at the edge of the water. Today, having gone through several renovations, it is possible to walk on the platforms that have been extended up to the far end of the cistern. In this way, you can also see the two huge Medusa heads that were used as a base for two columns at the rear end. The special light effects and the classical music that is sometimes played in the background increases the romanticism of the atmosphere as you walk between the pillars.

The cistern is 140 metres long and 70 metres wide. The 12 rows with 28 columns each add up to a total of 336 but, 90 of these were walled off in the 19th century and are not visible. They are approximately 4 metres apart and 8 metres high.

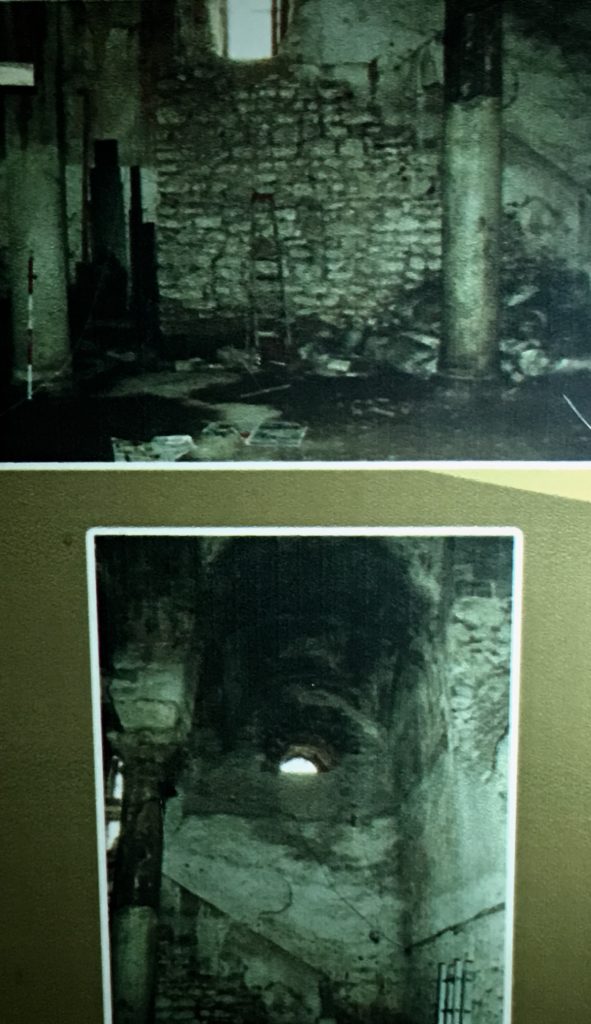

I believe the first time I visited the A Thousand and One Columns (Binbirdirek) or the Philoxenus Cistern was almost 30 years ago. It was nothing like it is today. I remember a small building on one side of a large square through which you went down a flight of steps to the cistern. Easy as it may sound, this was one of the few terrifying experiences I had in my life. Remembering it still gives me the creeps. First of all, because there was no lighting inside and daylight from the top of the stairs was coming from behind as you went down, it was pitch dark. I had my left hand on the wall while trying to feel the steps with my foot as I went down. If you could call them steps, that is. Just some shaky and worn out slabs of stone would be a better description. On top of all this, I was pregnant… I was terrified and full of resentment all the while I went down for what seemed like an endless time. Once we reached the floor and our eyes got used to the darkness, we could hardly make out the rows of columns rising out of the rubble and dirt in the cistern.

(4th century A.D.)

After going through a thorough restoration, the Philoxenus Cistern is currently open to the public and provides service as a café and a restaurant as well. It is a venue for weddings and all kinds of other organisations. Lately, it has also become a popular filming location for Turkish films and television series. It is stated that, thousands of truckloads of garbage and rubble were taken out of the cistern. The entrance has been moved to the adjacent street by means of a gallery and the slight slope at the door provides an easy access inside. With proper illumination, now you can fully admire the beauty of the Philoxenus Cistern.

The Philoxenus Cistern is named after the Roman senator who had it built in the 4th century. He was one of the senators Emperor Constantine forced to move to Constantinople when he decided to rebuild the city. Philoxenus commissioned a palace for himself close to the Hippodrome and this cistern was most probably built to supply water to the structure. The cistern is said to be more than 3500 square metres with 16 rows of 14 columns each. Out of the 224 columns, 212 of them have survived. 12 of the them have previously been walled off. The Turkish name, A Thousand and One Columns, is thought to have been given to express the abundance of the columns instead of its literary meaning.

The unusual height of the columns (12.4 metres) is revealed by the square pool right at the centre of the cistern which was made during the restoration. Looking down, you can see the approximately 5 metre section of the columns that is below ground level. All the columns have Greek signs on them which are thought to be marks left by the stonemasons who built the cistern.

The Philoxenus Cistern was not used during the Ottoman period. Several mansions were built on top of it at different times. The cistern dried out completely in the 16th century and was used as a yarn workshop for a long time.

The third important cistern that has survived to this day from ancient Istanbul is the Theodosius (Şerefiye) Cistern. Together with the Philoxenus (Binbirdirek) Cistern close by and the Basilica (Yerebatan) Cistern, it was part of a system that distributed the water coming from the Belgrade Forest to the Valens Aqueduct. According to experts, the three structures are interconnected and research on the subject is still continuing. The cistern, which was recently restored and opened to the public, was built by Emperor Theodosius II, between 428-443 A.D. This is a medium sized (1125 square metres) cistern supported by 32 pillars that are 9 metres high. Just like the Philoxenus Cistern, other buildings were built on top of it during the following centuries. The last of these was the Eminönü Town Hall which was pulled down in 2010. This extraordinary monument and historical heritage was discovered during the demolition. The beautifully restored cistern is now utilised as a concert hall and exhibition centre from time to time.

Encountering remnants of monuments from ancient times during constructions of new buildings is not uncommon in the Old City part of Istanbul. Some of these have fortunately been saved with the collaboration of the land owners with the High Council of Monuments and the Archaeological Museums of Istanbul. The optimal solution that is sought in these cases is the one that meets both the present-day needs of the owner and preserves the monument at the same time. Two examples of this kind of preservation are the cisterns under the Antik Hotel and the Nakkaş Carpet Shop.

The historical ruins under the Antik Hotel were found in 1984 while excavations for the foundation of the hotel were being made. It turned out that, the remains found at a depth of 12 metres belonged to a cistern built in the Late Roman and Early Byzantine period (450-500 A.D.). It was also found out that, an Ottoman structure was also built later on at this location, on top of the cistern. The hotel is now rising above the cistern without harming its original structure. Named as Antik Cisterna, it is now a part of the hotel where special organisations and exhibitions and art installations are hosted.

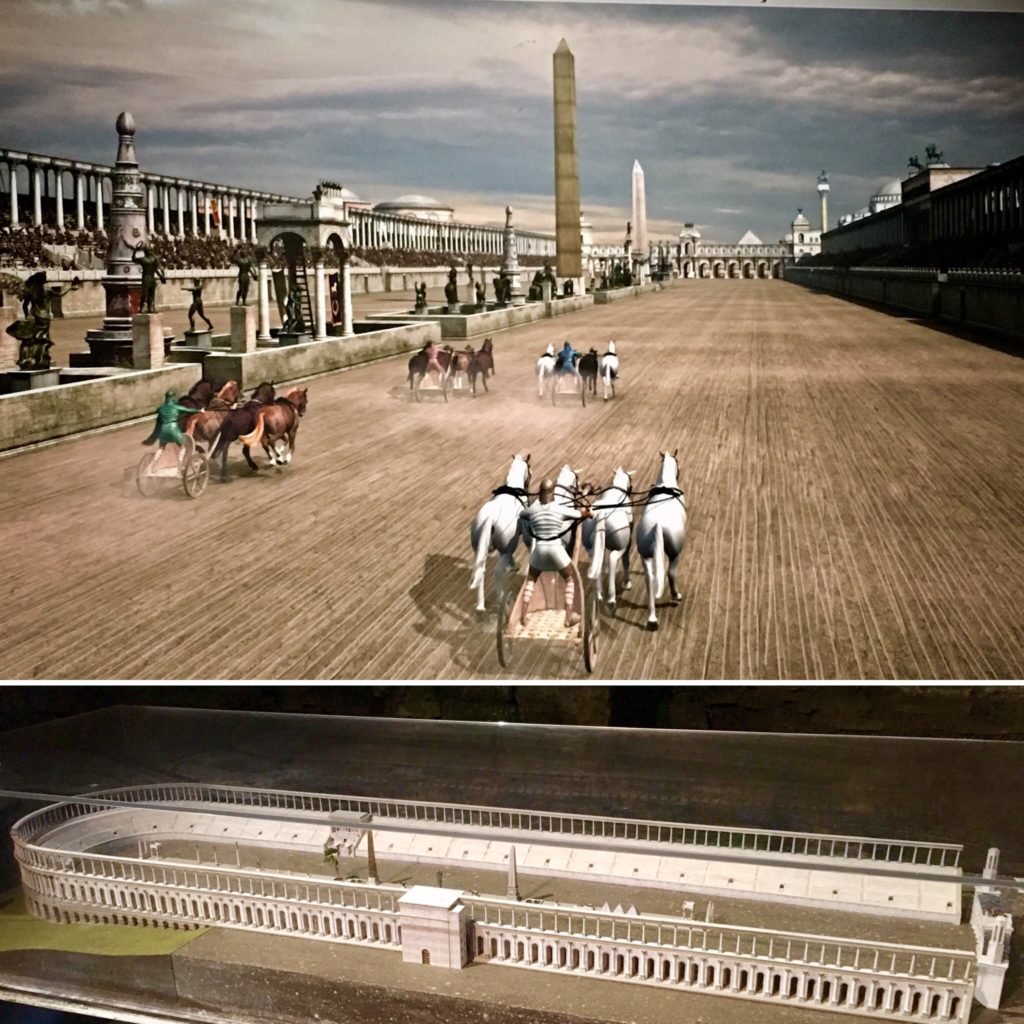

The basement of Nakkaş Halıcılık has a similar story. This carpet shop which is in Nakilbent Street, close to the Sultan Ahmet Square, has a cistern dated from the 5th or 6th century A.D. underneath. It is believed that, once it was part of the Byzantine Grand Palace complex. The dimensions of the cistern are 35 by 10 metres. This area is currently being used for concerts, exhibitions and meetings. At the time of our visit, there was a fabulous on-going exhibition on the now none-existent Hippodrome of Constantinople. The water that naturally accumulates in the cistern has to be emptied from time to time.

The Sultan Cistern at the corner of the Yavuz Selim Avenue and Naki Street in the Yavuz Sultan Selim district of Fatih is another good example for the rescued cisterns in the Old City. It is believed to be built during the reign of Emperor Theodosius I (378-395 A.D.) The dimensions are 29 by 19 metres with 28 columns. Seven of these are made of granite while the rest are white marble. You can see crosses and Greek letters on some of them. It was one of the important cisterns of the Byzantine era but, in time it became a warehouse for carpenters and yarn manufacturers. It stayed as a dilapidated and abandoned ruin until the year 2000 when it was taken under protection. The restoration took seven years. Now it is a venue for weddings, meetings, seminars and conferences.

The walls of the cistern are visible right below the Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque

Lastly, it must be noted that not all Byzantine cisterns were covered structures. Enormous open air water tanks are also considered to be cisterns even though these were in reality just water distribution pools. Out of the three such cisterns in Istanbul, the Aspar Open Air Cistern (Çukurbostan) next to the Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque on the Fifth Hill, in the Yavuz Selim district, is the most well-kept one. Originally, the dimensions of the cistern were 152 by 152 metres with a depth of 11 metres and the surrounding walls were 5 metres thick. Built in 457 A.D. by the commander Aspar, like the other open air cisterns, in time it became a market garden for growing vegetables, justifying its name in Turkish, Çukurbostan (meaning the market garden in the pit). Eventually, the place became a proper Ottoman district with its houses, streets, shops and mosque inside the cistern until, after several devastating fires, they were all pulled down in the 1950’s. Today, there is a park and a sports area inside the Aspar cistern.